Saltwater Foodways: Martha’s June Jottings

An early journal provides insights into 18th century Maine gardening and food

By Sandra L. Oliver

By Sandra L. Oliver

No, not that very modern Martha-a much earlier Martha, who lived on Maine's frontier out by Hallowell and Augusta at the turn of the eighteenth century. We're talking about Martha Ballard, midwife, health-care provider, mother, gardener, housewife, and prodigious diary keeper from 1785, when she was 50, until her death in 1812.

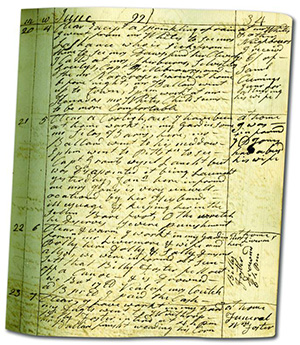

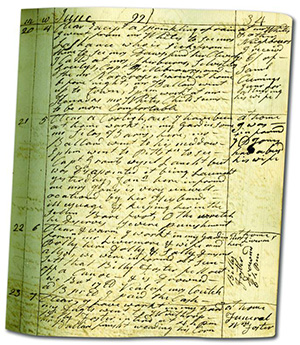

June 21, 1792 Martha Ballard's diaries are in the collection of the Maine State Library. This excerpt is from the first day of summer, June 21, 1792: "Clear, a Coolish air. I have been a' home, workt in my Gardin Some. Mr. Silas Barns here. Mr. Ballard went to his meadow. Ephm went to Pittstn to see Capt Grants vessel Launch but was disappointed, it being Launcht yester day." Courtesy of the Maine State Library

It is fun to snoop into someone's ancient diary, to catch the rhythm of their daily life, to note things that never change, and other activities so different from modern life that we're reminded that sometimes the past is like a foreign country. Martha Ballard's actual diary, made famous by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich's Pulitzer Prize-winning book, A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard and Her Diary, 1785-1812, resides in the collection of the Maine State Library in Augusta, Maine. Fortunately, the diary is available online, where the curious can browse through it. It survived, fragile as it is, because it was passed down in her family, and was preserved because genealogists value the many births and deaths that Martha recorded.

Ballard's journals continue to inspire gardens like this one planted by Eliza Soeth of Friendship, Maine. Photo by Lynn Karlin

I was drawn to it because it also is a wonderful way to learn about early gardens and food preparation.

Martha, bless her hand-knit stockings, wrote about what she cooked and ate between delivering babies and visiting the sick; sometimes falling off her horse en route. She wrote about perfectly familiar food: beef, pork, veal, salmon, corn, pumpkins, and such vegetables as cabbage, potatoes, and cucumbers. Less familiar are terms like "haslet," a now-archaic term for offal, the edible viscera of newly slaughtered animals, such as liver, kidneys, and sweetbreads.

She also recorded her housework, planting, harvesting, knitting and weaving, company visits for tea and overnights, visits from people seeking remedies, and community news: marriages, drownings, murders, court sessions, vessel arrivals and departures, funerals, and weather reports. In all during the 27 years she kept her journal, she wrote 9,965 entries.

This view of Augusta was sketched by Cyril Searle about 11 years after Martha Ballard's death and was reproduced in a history of the city printed in 1870. It shows the city from the east side of the river, much as it would have looked when she was alive. Courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Back in those days, Martha and others like her had to either grow or raise most of their own food, or barter for it. In June, year after year, Martha planted or transplanted beans, cucumbers, squash, turnips, radishes, beets, parsley, lettuce, a lot of cabbages-sometimes as many as 50 at a time, two or three times a month-plus "musk mellions," and watermelons, too. She wrote in 1801, as she did nearly every year, "I Planted Cucumbers and houghd peas." That year she cut potatoes for planting, a chore usually performed by her husband, Ephraim. Another year, she reported, "I have workt in my Gardin, planted bleu potatoes, 2 lb wt."

Corn was another field crop usually handled by her husband, but Martha reported shelling corn for seed, and planting some, too. She writes often about seed saving. Details of where in her yard she planted may have had to do with keeping track of what was cultivated for seed and what was grown for food. She also planted herbs for medicinal use.

Martha also recorded planting apple trees and setting out strawberries. She and her daughters picked wild strawberries; once she mentioned that they went to "the field" to pick after the washing was done, as if harvesting berries was recreation.

June 21, 1792 Martha Ballard's diaries are in the collection of the Maine State Library. This excerpt is from the first day of summer, June 21, 1792: "Clear, a Coolish air. I have been a' home, workt in my Gardin Some. Mr. Silas Barns here. Mr. Ballard went to his meadow. Ephm went to Pittstn to see Capt Grants vessel Launch but was disappointed, it being Launcht yester day." Courtesy of the Maine State Library

Ballard's journals continue to inspire gardens like this one planted by Eliza Soeth of Friendship, Maine. Photo by Lynn Karlin

This view of Augusta was sketched by Cyril Searle about 11 years after Martha Ballard's death and was reproduced in a history of the city printed in 1870. It shows the city from the east side of the river, much as it would have looked when she was alive. Courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Martha, bless her hand-knit stockings, wrote about what she cooked and ate between delivering babies and visiting the sick; sometimes falling off her horse en route.

Back in those days it was not enough just to produce food and store it. Someone needed to check on the inventory, pick out any spoiled things, check on brines, and monitor overall quality. Some years, Martha cleaned the cellar in June, repacking and re-storing. One year she wrote that she took some potatoes out of the cellar, washed them, and put them in a chamber to dry off.

Potatoes kept too long in a cellar, I have found by my own experience, will not only begin to sprout, but also to soften and get a little sticky. Following Martha's lead in May and June, I, too, examine my potatoes, snap off the sprouts, and lay them out in the sun for a couple of hours to dry before putting them back into their five-gallon buckets in the cellar.

The Ballards ate a lot of veal in June. They, or a neighbor, might kill a calf and often Martha recorded eating a roasted loin of veal. Alarming as it sounds, they also loaned and borrowed meat. Of course, they did not get or give the same piece back. Rather, they recorded carefully how many pounds they borrowed, and the same quantity was returned when they killed an animal. Calves born earlier in the year were ready for butchering by early summer; often male calves were harvested while females were kept to increase the herd. Small animals, like the 84-pound calf the Ballards killed in 1790, or the occasional lamb, were easily divided, shared, and consumed in warmer weather.

Freshly butchered animals meant a stretch of hard work, though, and required quick work in the days before artificial refrigeration. In 1796 the Ballards killed a calf. Martha cleaned the head and feet the same day, then was called to attend three births in a row. The next day she noted, she "came home at evn and do feel much fatagud [fatigued] but was obliged to Sett up and cook the orful [offal] of my Veal." Calf's head makes a fine soup, the feet yield a rich stock, and the offal, liver, spleen, tripe, sweetbreads and lungs, provided a few nutrient-rich meals.

The menu this bounty produced, included in 1796, "a loin of veal, bakt pudding and pork and beens for dinner." Once, on the last day of May, she wrote that she roasted veal for dinner, and made rhubarb tarts in afternoon, the only non-medicinal use of rhubarb that she recorded. Usually, she made a potion of it, often with senna, as a curative. It took rhubarb a few more decades to catch on popularly as a food fruit.

Fairly often Martha recorded eating pork and greens, but she gave no clue what sort of greens. We might surmise that since she planted cabbages and turnips for seeds, she cut some of the early sprouts to eat. She did not mention spinach or dandelions by name, though once she mentioned gathering greens as if they were wild.

Even though the Ballards produced much of their food, they bought food as well. Martha wrote about milking, making cheese and butter, as well as buying both, along with pork, corn, rye, and wheat. Occasionally the Ballards received these same items in return for some earlier favor or loan of food. Sugar, tea, coffee, chocolate, rum, molasses, "spirits," salmon, mackerel, codfish, even crackers and gingerbread ended up on the grocery list. Snuff, too, it must be said. Sometimes Martha was given items like this as pay for her midwifery and healthcare work. Special treats in the form of a lemon and an orange show up in her diary as gifts.

Martha baked bread, brewed beer, and made pies. She reported making a barrel and a half of beer at a time, quite possibly as a daily drink. Yeast needed the same day for baking bread meant baking and brewing were linked processes-beer created more yeast as a by-product.

When Martha and her husband were growing up in Massachusetts, the common daily bread was made of rye meal and cornmeal (called "indian"). Dense, dark, and nutritious, this bread, which was known as rye-and-indian, sustained generations of early New Englanders. The favored bread, however, was always white bread made from wheat flour. By the time the Ballards were living in Maine, three-grain bread, sometimes called brown bread, made of one third each rye, cornmeal, and wheat flour, was fairly common.

When Martha wrote, "bakt flower bread," she probably used wheat. When she wrote that she had baked flour and brown bread, perhaps she made the three-grain bread, or a loaf of white plus a loaf of rye-and-indian.

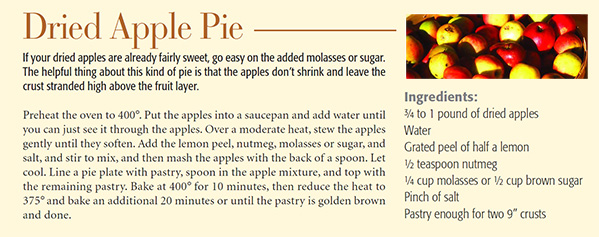

Surely she reserved wheat flour for cakes and piecrust. Like all good New England housewives of her time, and even ours, Martha baked pies, most often pumpkin, mincemeat, and apple. In June 1886, she made apple pie.

When Martha wrote, "bakt flower bread," she probably used wheat. When she wrote that she had baked flour and brown bread, perhaps she made the three-grain bread, or a loaf of white plus a loaf of rye-and-indian.

Apple pie in June? Did those apples stored in the cellar keep until June? Maybe. In June 1789, she sent a traveling friend off with apples and some other foodstuff. Quite possibly she meant dried apples. We know she dried apples because she wrote about it in October entries. Also sometimes in the winter she wrote about checking her stored apple supply, selecting some for sauce, and some to cut for drying.

As with potatoes, I follow Martha's good example with apples. Bringing bucketsful upstairs, I pick the apples over, toss the semi-rotten ones to the chickens, choose some for sauce, and dry others on skewers of wood supported by the sides of a deep baking pan set on the always-warm shelf of my wood-burning cookstove. They keep in a glass jar, good for snacking, cutting into fruit compote, and, of course, apple pie in June, long after the fresh apples are a mere memory.

Contributing Editor Sandra L. Oliver's most recent book Maine Home Cooking: 175 Recipes from Down East Kitchens (Down East Books, Rockport) was published in 2012.

Contained in several volumes, Martha Ballard's diary was transcribed and published in hardback in 1992 and also microfilmed. You can read the entries online at www.dohistory.org.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.