Blue Jays, and Lightnings, and Lasers, Oh My

There must be a couple of hundred small sailboats available new or used that would serve just fine on any Maine lake. In this issue, we narrow the choices down to just three: the Blue Jay, the Lightning, and the Laser.

Lightnings and Blue Jays—like Stars and Comets, Indians and Town Class, Thistles and International 14s—could be considered size variations on a theme. Both are Sparkman & Stephens designs, and Blue Jays are often referred to as “baby Lightnings.” Back in the heyday of one-design sailing, this mama and baby sailboat theme was common.

Blue Jays feature a complete sloop rig, which makes them a great boat for teaching sailing. MBH&H Publisher John K. Hanson learned to sail on this one, which he still owns and sails on Megunticook Lake in Camden. Photo by Art Paine

Blue Jays feature a complete sloop rig, which makes them a great boat for teaching sailing. MBH&H Publisher John K. Hanson learned to sail on this one, which he still owns and sails on Megunticook Lake in Camden. Photo by Art Paine

Blue Jays have an emotional connection for me. My twin brother and I built our first boat, a Blue Jay, at the age of 14 in our family’s garage. Back in the day, before one-designs were all popped out of a mold, each with a white hull and a colored deck, a youngster’s first boat was a unique and treasured thing, more so of course if he and his brother built it themselves.

Blue Jays were inspired by Drake Sparkman and designed by his firm, Sparkman & Stephens. The former chair of his yacht club’s junior sailing program, Sparkman intended the boats to be used to teach sailing. Accordingly, Blue Jays feature a complete sloop rig with a mainsail, jib, and spinnaker. This setup provided the essential lines for two children to learn how to trim and coordinate sails. The boats, which have roomy open cockpits and no seats, can easily hold three kids or two adults.

The original design (1947) called for the boats to be easily built with readily available quarter-inch-thick plywood (the plans are still available from the International Blue Jay Class Association). A fiberglass version became available in the 1960s.

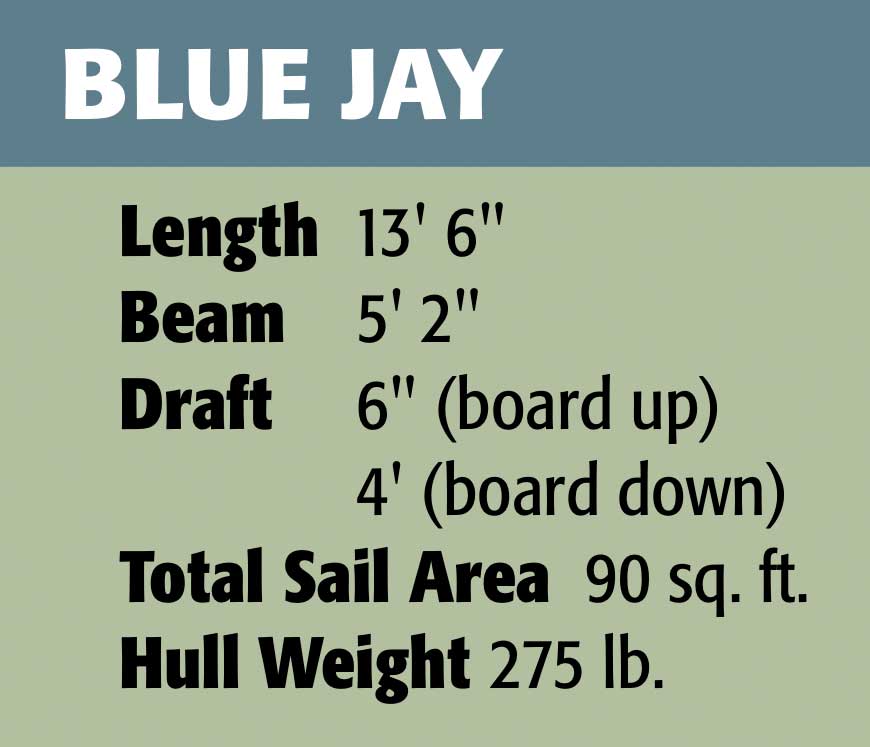

At 13'6" long with a draft of just 6 inches—or 4 feet with the centerboard down—the Blue Jay makes a great lake boat. Small and light, these boats can be trailered behind any old car, kept on a mooring, pulled up on the beach or just tied up at the dock. The small sail plan is manageable by kids of average size and limited strength, but in a strong wind this flattish-bottomed box still can get up and plane. It can capsize, too—although that takes a fair amount of effort. When you are just 14 or so, if the water is midsummer warm, capsizing just adds to the fun.

Now that I’m fully grown, it is easy for me to rig a Blue Jay on Lake Megunticook and sail it alone. Given my history with these boats, an afternoon sail in a Blue Jay is a special pleasure. The beauty of this design is that anybody can delight in the Blue Jay’s lively maneuverability, the enjoyment of hiking hard and making the boat point and go to windward. When I pull the centerboard halfway up, hike out hard, and hear those staccato little pulsations reverberating up from the cutwater, I’m buff, I’m young, and I’m ineffably happy.

The Blue Jay’s spacious cockpit has room for three or more kids or adults. Photo by Jamie Bloomquist

The Blue Jay’s spacious cockpit has room for three or more kids or adults. Photo by Jamie Bloomquist

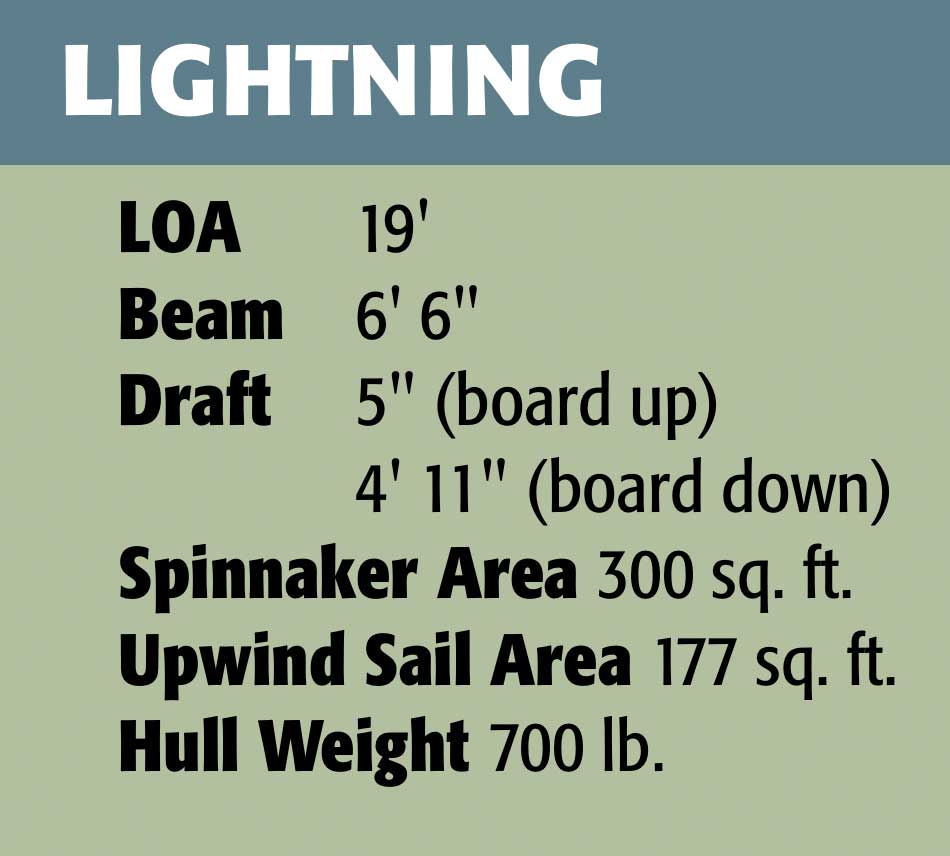

To a Blue Jay sailor, the 19-foot Lightning might seem like a big and elegant yacht. The Lightning is a more elaborate boat to build because, prior to being offered in fiberglass, it was meticulously planked with top-quality softwood. The bottom is shaped like a very shallow arc of a circle, although—like a Blue Jay—the Lightning has a hard chine and flat topsides.

To a Blue Jay sailor, the 19-foot Lightning might seem like a big and elegant yacht. The Lightning is a more elaborate boat to build because, prior to being offered in fiberglass, it was meticulously planked with top-quality softwood. The bottom is shaped like a very shallow arc of a circle, although—like a Blue Jay—the Lightning has a hard chine and flat topsides.

While the Blue Jay’s centerboard is made of common plywood or laminated wood, the centerboard of its mama Lightning is galvanized or stainless-steel plate, only 3/8 of an inch thick. This metal board helps make the boat a little more stable. It also happens to be a good choice for rocky Maine lakes because it can bash into a rock without expensive damage. The thin centerboard has minimal resistance at high speed, allowing a Lightning to plane in good winds almost any time the spinnaker is up.

Lightnings, in addition to being one of the world’s most competitive dinghy classes, are remarkably comfortable for day sailing. Photo by Art Paine

Lightnings, in addition to being one of the world’s most competitive dinghy classes, are remarkably comfortable for day sailing. Photo by Art Paine

Designed in 1938, Lightnings were specifically configured to be sailed by a crew of three, although I know someone who restored one and sails it alone on Panther Pond and Sebago Lake. Lightnings point very close to the wind, and easily hit six knots. About the only negative thing I can say about Lightnings is that you need a biggish lake or you will soon run out of water. Also, like its baby sister, a Lightning can capsize.

Designed in 1938, Lightnings were specifically configured to be sailed by a crew of three, although I know someone who restored one and sails it alone on Panther Pond and Sebago Lake. Lightnings point very close to the wind, and easily hit six knots. About the only negative thing I can say about Lightnings is that you need a biggish lake or you will soon run out of water. Also, like its baby sister, a Lightning can capsize.

Modern fiberglass Lightnings are low maintenance. They are usually fitted with side ballast chambers or buoyancy bags so they can, with lots of grunting and groaning, be re-righted after capsizing by a crew of three. It helps to have some clothing or rags to stuff into the top of the centerboard trunk, and a nearby powerboat can be helpful. The fact is that I have sailed my buddy’s Lightning all around Panther Pond, just him and me, in all kinds of wind, and never had any trouble.

There are many high-tech expensive dinghies that can sail circles around a Lightning, but for me, when I sail a Lightning on a lake and heel her over displaying the flashy varnished seats and ribs and floorboards to lakeshore dwellers, I feel like John Beresford Tipton cruising downtown in his Duesenberg Touring Car.

Lasers have earned their status as one of the world’s most popular single-handed dinghies; they are light enough to move around on a car top or trailer, easy to rig, and a total blast to sail. They come with both smaller and larger rigs, depending on the size of the sailor.

Lasers have earned their status as one of the world’s most popular single-handed dinghies; they are light enough to move around on a car top or trailer, easy to rig, and a total blast to sail. They come with both smaller and larger rigs, depending on the size of the sailor.

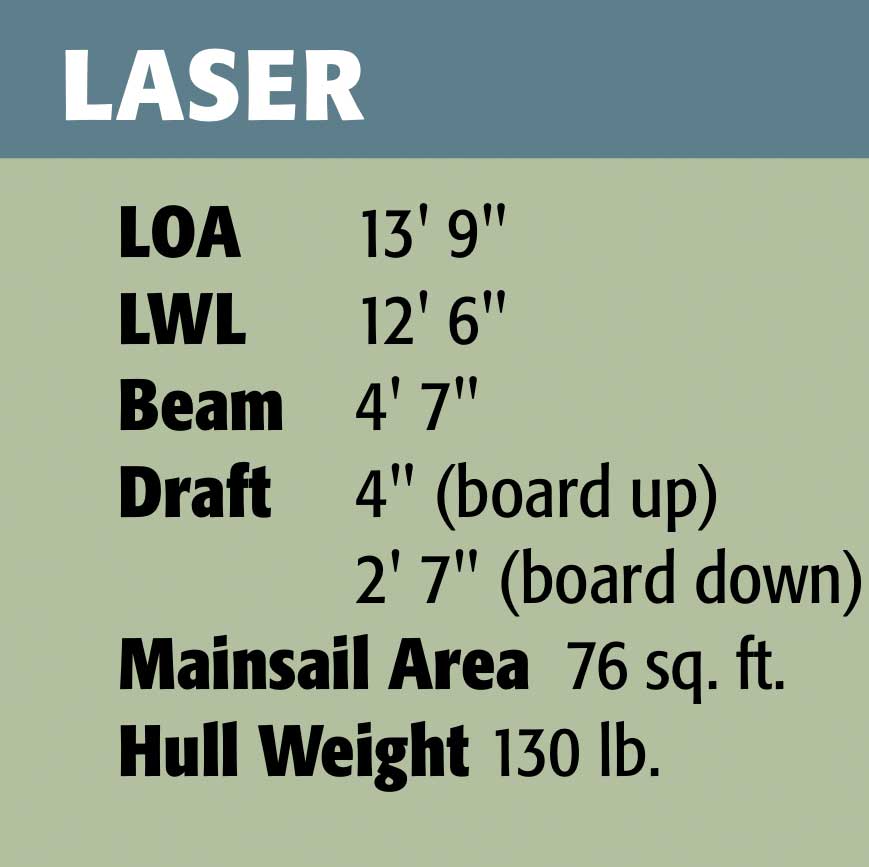

My third, and far more obvious, choice for a practical lake sailboat is the ubiquitous Laser. You will find these stashed away, inverted, gelcoat faded, around the perimeter of nearly every Maine lake. Lasers are one of the world’s most popular single-handed dinghies. The story goes that designer Bruce Kirby sketched the original concept on a table napkin in the late 1960s during a discussion about making a boat small enough to be carried on the roof of a car.

My third, and far more obvious, choice for a practical lake sailboat is the ubiquitous Laser. You will find these stashed away, inverted, gelcoat faded, around the perimeter of nearly every Maine lake. Lasers are one of the world’s most popular single-handed dinghies. The story goes that designer Bruce Kirby sketched the original concept on a table napkin in the late 1960s during a discussion about making a boat small enough to be carried on the roof of a car.

The design was perfect in terms of performance, and also perfect in simplicity: The easy-to-build hull mated to the easy-to-build deck lid by means of a cleverly turned-down edge. The one slipped over the other and all that was needed to mate the parts together was a little bit of goo. (One might say it was a goo-ed idea!) Over 200,000 of these hulls have been manufactured and they can be found all over the world.

The Laser mast is just a round aluminum tube, or actually a pair of tubes that fit together. The single sail slips down over this pole before it is stepped, and since the sleeve rotates around with the sail, it’s all very aerodynamic. This is far easier and way less prone to trouble than you might imagine. In most any other boat you would have a halyard. But the Laser flips over and unflips with ease. If a thunderstorm looms, instead of dropping the sail you can intentionally capsize for a spell. The boat floats high and visible, becoming one huge life preserver.

Laser hulls are light enough (130 pounds) that one person can easily drag it back and forth from the shore to beach or woods. I owned a Laser at one time and by myself could haul it off the top of my car, where it customarily lived. I was a lot younger then….

If you get really good at sailing a Laser, you can qualify to compete in the Olympics. There is a somewhat smaller mast and sail combo available and whole gaggles of thusly-rigged Lasers form a separate official class, the Laser “Radial.” This is a great equalizer for the light and the small of stature.

But all that is racing stuff, and what I really wanted to emphasize is that there probably isn’t a boat in the whole world that is as much fun to just sail as a Laser. That’s what I’m talking about!

Flitting around at high speed on a windy blue day on a whitecapped Maine lake, your eyes just inches above the water. Some people can even gybe without catching the mainsheet under the corner of the transom! Not me—not always. But who cares?

We are on a lake, it’s midsummer, it’s hot, and a periodic dunking just washes off the sweat.

Bliss!

Contributing Author Art Paine is a boat designer, fine artist, freelance writer, aesthete, and photographer who lives in Bernard, Maine.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.