Sir Ferdinando Gorges and His Impossible Dream of Maine

Sir Ferdinando Gorges’s love for Maine was ignited one fine summer day in July 1605, when a small ship, the Archangell, put in at Dartmouth Harbor on England’s southwest coast. The ship’s captain, George Waymouth, then in his early 20s, had just returned from a voyage to the New World. During a courtesy call on Sir Ferdinando, who commanded the fort at the neighboring port of Plymouth, Waymouth regaled him with stories about the things he had seen along the coast of what is now Maine. Gorges, then about 37, had spent the better part of a decade on the alert for enemy attack by sea, but a peace treaty had been signed with Spain just a year earlier. Now Gorges—a military man, knighted on the battlefield, and owner of a small fleet of journeyman vessels—was bored and eager for new adventure.

Waymouth provided it. Scion of a seafaring and shipbuilding family, Waymouth, after an unsuccessful quest to find the fabled Northwest Passage to China in 1602, had become obsessed with the idea of creating a permanent settlement in America. This was a scheme the English had not seriously entertained since the vanishing of the colony on Roanoke Island, off the coast of what is now North Carolina, in 1590.

Sir Ferdinando, who until that day had shown no interest in the New World, must have been enticed by Waymouth’s stories. The Archangell had set sail in March 1605, and in May made landfall at an island the voyage’s chronicler recorded as Monihiggan. There they harvested berries, collected firewood, and caught fat, sweet-tasting cod. They explored a river (probably the St. George) they praised as the richest and most beautiful in all the world—excepting, of course, their own River Thames.

Even more fascinating than the tales of this American paradise were the five Abenakis—Sassacomoit, Tahánedo, Skicowáros, Amóret, and Mannedo—whom Waymouth had captured and brought home with him, likely the first North American Indians to set foot on English soil. Three of them came to live with Sir Ferdinando, his wife Ann, and their sons, John and Robert, age 10 and 12.

That winter of 1606, Gorges focused on America and the Indians. He learned their language, taught them English, and listened as they described the people, geography, and commodities of their homeland. He found himself deeply impressed and later mused that the Indians were far more civil than his “rude” fellow Englishmen.

A grand idea began to form in his mind. The second son of a gentleman of modest fortunes, he had never attained the wealth and position of others in his set. Nor could he claim any surpassing achievement, certainly nothing to rival that of his predecessor at Plymouth Fort, Sir Francis Drake, who had circumnavigated the globe by the age of 40. Gorges began to imagine his future as the founder of an English realm in America, an Eden sprawling with Tudor-style castles, a colony blessed by King James I, with Gorges himself perched on a royal governor’s throne.

Sir John Popham (1531-1607) was Sir Ferdinando’s partner in the Popham settlement of 1607.

To further his scheme, he formed an alliance with a prominent member of the English gentry, Sir John Popham, who was lord chief justice, essentially England’s top judge. Popham, who had taken in the other two Abenakis, also was intrigued with the idea of an American settlement. Viewing America as a place where England’s unemployed, disenfranchised, and disagreeable could get a new start, he petitioned the King for the rights to develop the American coast on England’s behalf. Those rights were duly granted to a new organization that Popham and his associates formed, called the Virginia Company.

Sir John Popham (1531-1607) was Sir Ferdinando’s partner in the Popham settlement of 1607.

To further his scheme, he formed an alliance with a prominent member of the English gentry, Sir John Popham, who was lord chief justice, essentially England’s top judge. Popham, who had taken in the other two Abenakis, also was intrigued with the idea of an American settlement. Viewing America as a place where England’s unemployed, disenfranchised, and disagreeable could get a new start, he petitioned the King for the rights to develop the American coast on England’s behalf. Those rights were duly granted to a new organization that Popham and his associates formed, called the Virginia Company.

Popham and Gorges swiftly set about raising funds, securing ships, laying in supplies, and recruiting men to ship out and live in America—but neither chose to go themselves. Sir John was in his mid-70s and ill. Sir Ferdinando suffered terribly from seasickness. They chose Sir John’s nephew, George Popham, to serve as president of the colony. He would be assisted by Raleigh Gilbert, son of an earlier adventurer, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, a half-brother of Walter Raleigh.

The Popham-Gorges ships, the Gift of God and Mary and John, departed Plymouth, England, at the end of May 1607 and dropped anchor off the coast of Maine in August. The crew chose a settlement location at the tip of Sabino Point, on the Sagadahoc River (now the Kennebec), protected from the sea and with easy river access. They wasted no time getting to work, following plans that called for a fort, chapel, buttery, bake house, guardhouse, and several private lodgings.

The intention was for the settlement to become a revenue-producing, self-sustaining venture through fur trading with the Indians and the harvest of commodities, particularly timber and sassafras—then considered a potent cure for everything from stomach ache to infertility. But there was no sassafras that far north. And, although they had brought Skicawarros with them and he sought to reconnect with Tahenedo, who had been returned to America by an earlier voyage, the Indians did not prove eager to establish trade relations with the English—at least in part because of the well-remembered Waymouth kidnapping. The winter was terribly cold. Supplies ran short. George Popham died, leaving the headstrong Raleigh Gilbert, then about 26, in charge.

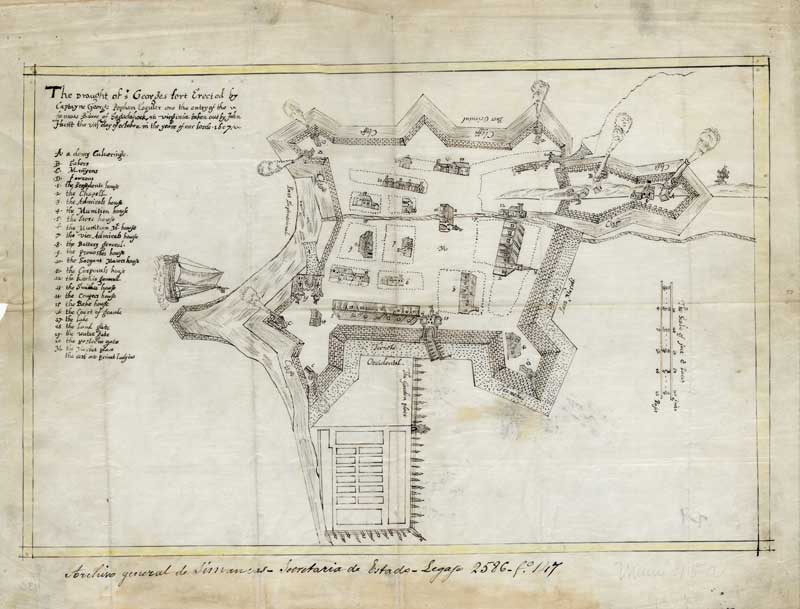

This map shows the elaborate, unrealized, plan for the Popham Colony fort. It is a 19th century copy of the original, which is in the Spanish archives in Simancas, Spain. Collections of Maine Historical Society, courtesy of VintageMaineImages.com item #7542

This map shows the elaborate, unrealized, plan for the Popham Colony fort. It is a 19th century copy of the original, which is in the Spanish archives in Simancas, Spain. Collections of Maine Historical Society, courtesy of VintageMaineImages.com item #7542

The final straw came in the spring of 1608, when news arrived that Gilbert’s older brother, John, had died. Raleigh Gilbert, next in line for inheritance, decided to return to England to look after the family estate and the entire crew sailed home with him. The Popham Colony, as it became known, had one signal accomplishment: construction of a sprightly pinnace named Virginia that they sailed back to England.

The failure of the colony came as a terrible blow to Sir Ferdinando—a “wonderful discouragement” as he called it. Adding to his dismay, another Virginia Company group had been successful, establishing a colony at Jamestown in 1607 that survived.

For seven years, Gorges resisted the temptation to try another American venture. But in 1614, John Smith, who had just returned from an unsuccessful whaling venture to New England, convinced Gorges to support a new settlement scheme. Smith’s plans went awry, but Sir Ferdinando’s passion had been rekindled. In 1622, he sought and received a grant for a huge parcel of land in New England, which he dubbed the Province of Maine. From that day forward, to the end of his life, Gorges spent much of his time and most of his money (largely supplied by his wives, of which there were four) trying to develop an English colony in Maine.

He might have succeeded, but for one fundamental miscalculation: he believed that the English social and political model could be successfully transplanted into America. Gorges imagined a cluster of interconnected colonies, each with a near-feudal owner, under an appointed governor, all loyal to the English king. But, as time went on, and settlement proliferated in Massachusetts and Virginia, the model that achieved success in America proved to be quite different—based on representative government and individual rights. Sir Ferdinando died in 1647, never having laid eyes on America or realizing even a part of his dream of a royal realm in the New World. The province of Maine passed to Ferdinando’s grandson, also Ferdinando, who, in 1677, sold the rights to the Massachusetts Bay Colony for £1,250.

Sir Ferdinando Gorges has been called “the father of English colonization in North America,” but is perhaps better described as a Don Quixote, a quester who chased a romantic dream of English royalism in a garden of Eden where democracy eventually flowered instead.

Fort Gorges was built during the Civil War to protect Portland Harbor, but saw no action. Like its namesake, it remains as a curious landmark, whose origins are largely forgotten. It is shown here with the 1924 schooner Bagheera in the foreground. Photo by Corey Templeton

Fort Gorges was built during the Civil War to protect Portland Harbor, but saw no action. Like its namesake, it remains as a curious landmark, whose origins are largely forgotten. It is shown here with the 1924 schooner Bagheera in the foreground. Photo by Corey Templeton

Today, Sir Ferdinando is memorialized in Fort Gorges, the grey stone pile standing knee-deep in Portland Harbor. It was built to protect the peninsula during the Civil War, but saw no action. Now it stands as a curious landmark—isolated, proud, and largely forgotten, just like its namesake.

John Butman writes and speaks about business through the lens of the social sciences. His most recent book, with co-author Simon Targett, is New World, Inc.: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (Little, Brown, 2018). He lives in Portland and summers on Bailey Island.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.