Sea Tales at the Big Table

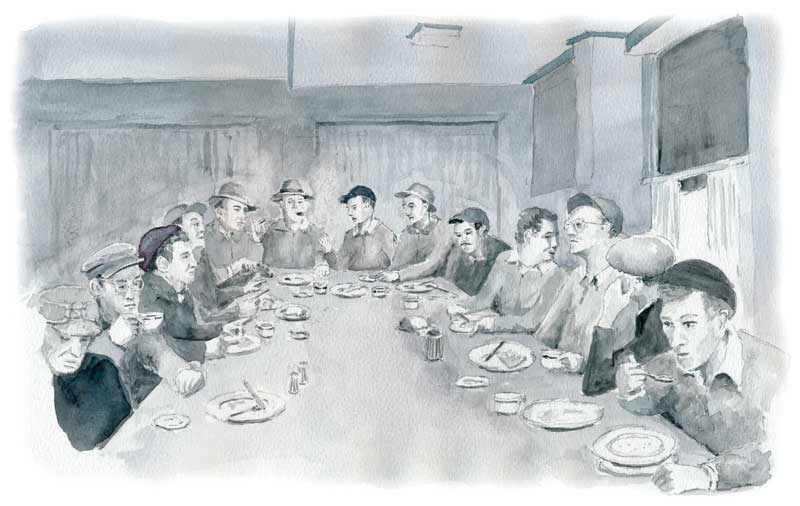

Illustration by Ted Walsh

Illustration by Ted Walsh

The place names of towns and villages on the coast of Maine tell stories about themselves. In the 19th century, Rockland supplied the lime for the first brick and stone buildings in the eastern United States and earned its name. But by the time the lime kilns shut down, Rockland was a vibrant fishing center, with access to some of the richest grounds on Georges Bank. That’s how I found the city—the only rocking we did was out at sea fishing.

There was a ditty back then: “Camden by the Sea, Rockland by the Smell.” It alluded to the aroma produced by the reduction plant that made fish meal and fish oil from the waste generated by Rockland’s fishing industry. From the end of World War II, when the Rockland beam trawlers chased the redfish all the way to the Straits of Belle Isle, until 1985, when the Hague Line cut Rockland boats like the O’Hara trawlers off from the Northern Edge of Georges Bank, fishing and fisherman owned the town.

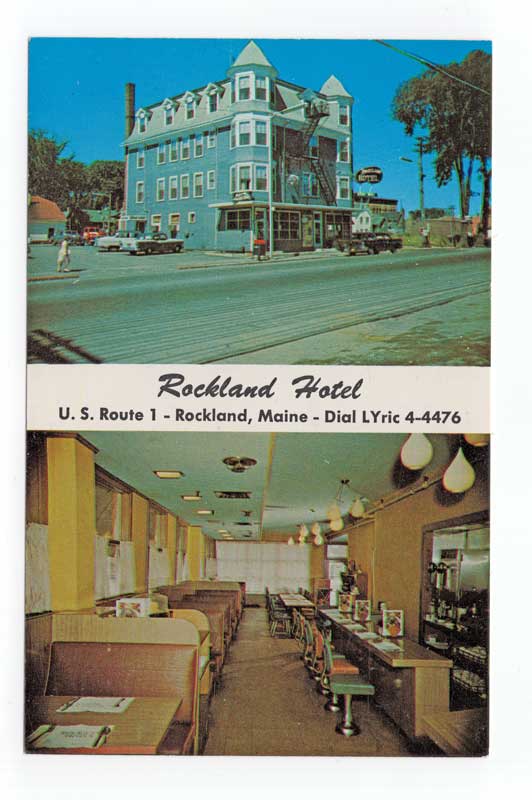

Fishermen gathered at the opposite end of this dining room at the Wayfarer. The building, which still stands, opened in the 1890s as the Maine Central Hotel. Image courtesy Brian Harden / Rockland Historical Society

Back then there was a restaurant and bar called the Wayfarer on the corner of Rockland’s Union and Park streets. Not as infamous for brawls as the Thorndike or the Oasis in those days, the Wayfarer offered many fishermen a refuge while on land, a place where we could speak our language and be understood. The dining room was dominated by a big table, at least 16 feet long, reserved for fishermen, and we all sat there together, no matter what boat we worked on. The menu included favorites from the boats’ galleys, such as corned hake, and fish cakes for breakfast, and when the howling winds drove all the boats into port, that table was full and raucous.

Fishermen gathered at the opposite end of this dining room at the Wayfarer. The building, which still stands, opened in the 1890s as the Maine Central Hotel. Image courtesy Brian Harden / Rockland Historical Society

Back then there was a restaurant and bar called the Wayfarer on the corner of Rockland’s Union and Park streets. Not as infamous for brawls as the Thorndike or the Oasis in those days, the Wayfarer offered many fishermen a refuge while on land, a place where we could speak our language and be understood. The dining room was dominated by a big table, at least 16 feet long, reserved for fishermen, and we all sat there together, no matter what boat we worked on. The menu included favorites from the boats’ galleys, such as corned hake, and fish cakes for breakfast, and when the howling winds drove all the boats into port, that table was full and raucous.

In air rich with the smells of coffee, cigarettes, and cooking fish, amid the clatter of plates and cutlery, crewmen old and young traded stories that impressed and entertained, but also bonded us, sometimes touching on the losses of friends and family.

One guy, so vain he had his dentures made uneven and capped with gold so no one would know they weren’t his own teeth, told a story of how they used to wear suits and ties down to the boats, and change into their fishing gear once aboard. “Eddy came down, nice suit, tie, hat, and he starts down the ladder. We watch him go right past the boat right into the water. He was so drunk he was up to his waist before he knew he was in the water!”

Another told how his uncle brought his wife from New York out to Matinicus, an island 20 miles off the coast. “He told her they had street cars and movie theaters out there. When she got there and seen they didn’t even have electricity she sat on the wharf crying until dark. He told her he had a refrigerator, when she finally come to the house she asks, ‘where was the refrigerator?’ he showed her a lobster crate!”

There was never a shortage of tales of tragedy, and inevitably someone would mention the Snoopy. Many at the table had had relatives and friends aboard the scalloper in 1965 when it ventured down off the coast of North Carolina in search of better fishing. One night the Snoopy’s crew hauled their gear and found themselves tangled up with a World War II torpedo.

“My stepfather was up forward and it blew him clear out of the wheelhouse,” says Jimmy, a young fisherman whose own tale would later be told at the same table.

“I heard they called the Coast Guard, and the Coast Guard told them to stand by, leave it in the water,” one fisherman chimes in as a waitress carrying two coffee pots fills everyone’s mugs and the conversation continues in a haze of cigarette and pipe smoke. “But they wanted to get back fishing, so they tried to bring it aboard, that’s when it blew.”

“I don’t know,” says Jimmy. “My stepfather passed, and he didn’t remember exactly what happened. He was up forward and it just blew him clear off the boat. Then there weren’t no boat.”

The rich fishing grounds of the Northern Edge and Northeast Peak of Georges Bank are said to be the only reason Rockland ever became a fishing port, because it was the closest to them. When the World Court at the Hague drew the line that gave those grounds to Canada, everything started to change in Rockland.

“We went all the way to the Grand Banks,” Tommy says one morning to a table full of fishermen in port due to the weather as Hurricane Gloria churns up the coast. “Five days steam to get there, five days fishing, and five days back.”

“I used to go down there with Ernie Kavanaugh, swordfishing,” an old timer says, referring to anything to the east as “down.”

“A pile of yellowtail down there,” says Tommy. “We had to gut them.”

“Gutting flatfish?”

Everyone at the table leans forward, astonished at the tedious idea of gutting flounders.

Rumor around the table was that the crew shared up well. We heard ten grand apiece, but Tommy didn’t say.

Jimmy later went on a small boat out of Port Clyde, and it was a somber table when his story came back to us.

“I guess they got a bag of dogfish,” says somebody. “Too heavy for that little boat, but they figured they’d try and bring it aboard and see if there was any flats in there. There weren’t no sea on, it was calm, but I guess it was just too much and it rolled them down.”

Fishermen at the time were working under a management plan that gave them a limited number of days at sea; this crew needed to make those days count so they tried to bring aboard a net full of dogfish—dense and heavy—in the hopes that it also held some valuable species.

“They found Jimmy the next day hanging onto a pen board, but he was gone.” There is quiet at the big table. “Funny thing, and I heard this from the Coast Guard, they didn’t put it in the report. They said there was whales circling him when they found him.”

“Whales? What kind?”

“I don’t know, they just said whales.”

Rockland no longer smells of fish, the reduction plant having been closed in the late 1980s. The table and the Wayfarer are long gone and thousands of stories drift away unremembered. Just a few endure: Eddy coming down that ladder into the water, and Jimmy being circled by whales.

Paul Molyneaux lives in East Machias and has written about commercial fishing in the New York Times and other publications. He is the author of A Child’s Walk in the Wilderness, published in 2013 by Stackpole Books.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.