Stonington’s “Bookmark Lady” Was a Relentless Artist

Article images courtesy Christina Shipps

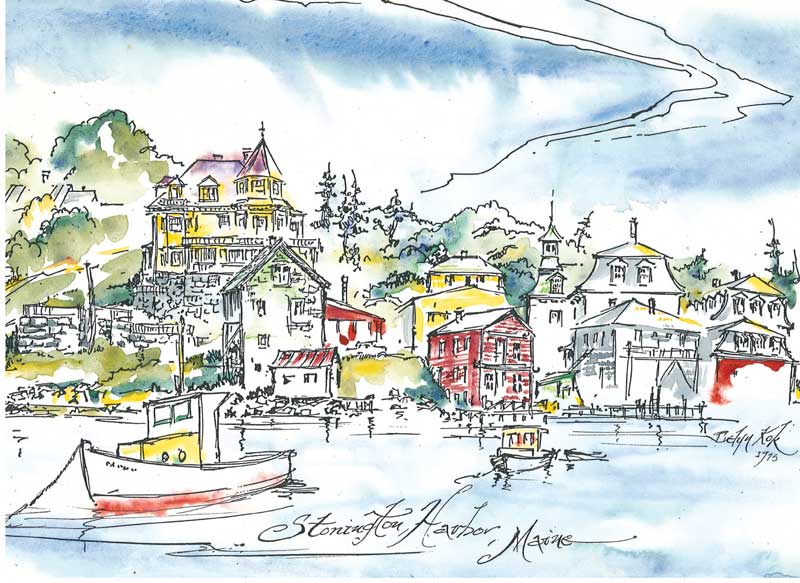

Stephen Taber, pen-and-ink watercolor, Evelyn Kok.

Stephen Taber, pen-and-ink watercolor, Evelyn Kok.

When the Stephen Taber sailed into Stonington years ago, the windjammer’s captain would send passengers ashore in a longboat. From the bustling fishing port’s pier, the visitors found their way to a small, silvered-clapboard structure hugging the waterfront. Awaiting them there was Evelyn Kok.

A slender, sprightly woman, Kok welcomed them into her studio. Passing through French doors, the Taber’s passengers stepped into another world. Inside the gallery, the artist’s watercolors brightened the former blacksmith shop. Many of the Taber’s passengers would purchase one of Kok’s hand-painted bookmarks as mementos of their adventure aboard the 19th-century ship. The page holders depicted Taber and other schooners and marine elements such as seagulls, starfish, and lobster traps. Each was a miniature work of art.

Bookmarks like The Purple Fish were all that were for sale in the Stonington gallery.

Bookmarks like The Purple Fish were all that were for sale in the Stonington gallery.

A musician, Kok might pick up a guitar or flat-back lute and entertain visitors with a bouncy tune that she composed to salute the tall ships. She wrote songs—music and lyrics—to celebrate each of the 13 windjammers that put into Stonington each summer.

“Every breeze on the seas loves the Taber and they sing her to sleep every night fine as she rests from a day of proud labor,” goes her ode to the Stephen Taber. The 153-year-coaster—still plying Maine waters today—is the nation’s oldest continuously working sailing vessel.

Known as “the Bookmark Lady of Stonington,” Kok and her musicologist husband, Jan, migrated annually from 1968 to 2011 to Stonington from their winter home in Maine’s northern potato-farming town of Presque Isle. The Taber, Angelique, Grace Bailey, J&E Riggin, Victory Chimes, American Eagle, and other schooners became Kok’s muse. In pen-and-inks, she captured the majestic ships on a broad reach, close-hauled, and on other points of sail, roaring down the Deer Isle Thorofare.

Kok also painted the wild coastal scenery and its inhabitants going about their lives. From sketches to portraits, she produced a wealth of artwork. Wholly absorbed in the creative process, she spent summers observing and sharpening her use of pens, pencils, brushes, ink, and paint to catch the shifting fog, hurtling clouds, cresting breakers, windswept trees, and other swiftly changing scenery.

After graduating from college in 1942, Kok spent the summer living with and painting Cree Indians in northern Quebec. Her watercolor above depicts daily life in the James Bay encampment.

After graduating from college in 1942, Kok spent the summer living with and painting Cree Indians in northern Quebec. Her watercolor above depicts daily life in the James Bay encampment.

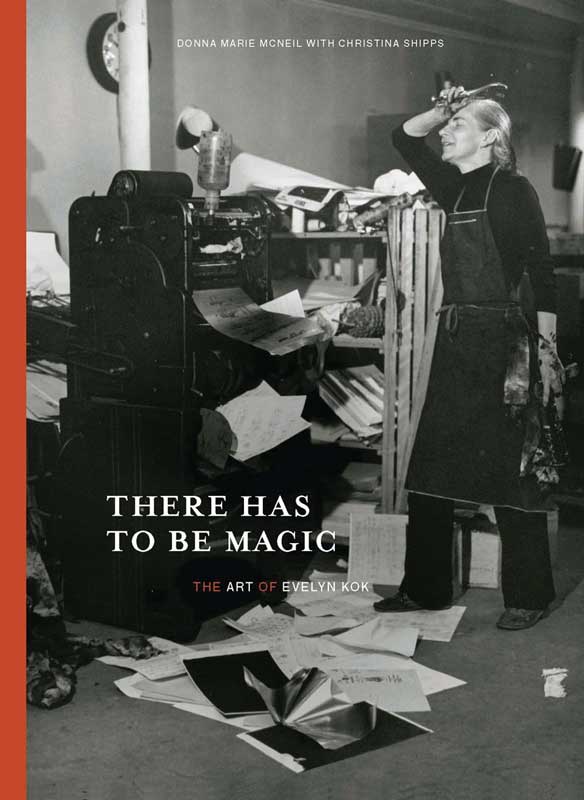

Art historian Donna McNeil discovered Kok’s work on a 2006 visit to Stonington and ended up co-authoring a book in 2018 about her life and work with Kok’s niece, Christina Shipps. There has to be Magic: The Art of Evelyn Kok (2017, Maine Authors Publishing, Rockland, Maine) won the Maine Writers & Publishers’ Excellence in Publishing Award as part of the organization’s 2018 Maine Literary Awards.

“In spite of this self-confidence and relentless creative output, Evelyn Kok never sought to be famous. She never engaged in the gallery or museum systems, the classic pathways for artistic notoriety and success. Evelyn simply was,” summed up McNeil, the former director of the Maine Art Commission and now the director of the Ellis Beauregard Foundation. “The story of Evelyn Kok is the story of untold numbers of individuals who find themselves compelled to create. She was irrepressible in this and faithful to her need. Unmotivated by fortune or recognition, Evelyn embraced the creative life exactly on her own terms.”

Through the story of Evelyn Kok, McNeil and Shipps recognize Kok as a notable Maine artist by chronicling her artistic journey. Shipps had inherited The Gallery of the Purple Fish—now known as The Art of Evelyn Kok Gallery—and Kok’s artwork after her aunt’s death at age 91 in 2014.

A metalsmith, Shipps led a successful corporate career in New York’s jewelry manufacturing industry before moving to Stonington where she ran The Inn on the Harbor for 23 years.

Here is her colorful depiction of the Stonington waterfront.

Here is her colorful depiction of the Stonington waterfront.

“No one knew how vast my aunt’s talent was and what subject matter she covered,” she said. “I was and am immensely proud of my auntie and wanted the world to know how brilliant she was.”

When McNeil first chanced upon The Gallery of the Purple Fish in 2006 and discovered Kok and her artwork, a series of expertly drawn and richly painted gouache medical illustrations, mounted on boards and displayed high on a shelf, caught her eye.

“They possessed a surprising balance of force and delicacy. I remember the pull on me—‘God those are beautiful’—and the need to get closer,” recalled McNeil in the preface to The Art of Evelyn Kok. She wanted to buy the illustrations, but the offer was politely refused by their white-haired creator, who was busily sketching a schooner moored in the harbor. Actually, none of the pen-and-ink watercolors covering the gallery’s walls were for sale. The hand-painted bookmarks were the exception and a bargain—the diminutive pieces sold at $1.75 apiece.

Kok, McNeil learned from Shipps, previously had been a highly regarded medical illustrator. She worked fresh out of art school from the mid-to-late 1940s through 1951. Graduating from Boston’s School of Practical Arts, she was hired by an innovative chest surgeon, who was known for performing the world’s first successful lung removal and achieving other major medical advances in treating pneumonia, bronchitis, tuberculosis, and lung cancer. Clad in a surgical gown, she sketched procedures from above, peering over the surgeon’s shoulder while he performed surgeries in the operating theater at the New England Deaconess Hospital in Boston. Her ink and painted illustrations, recording in detail the operation and the surgeon’s techniques, were disseminated and referred to by surgeons and research scientists worldwide.

“They required a finely focused eye and demonstrate Evelyn’s rare ability to cast her observations onto paper with scientific exactitude,” McNeil marveled. “The medical illustrations from this period are beyond mere clinical representations. They contain something more, a beauty and sensitivity to form, color, and composition, which transforms them into fine art, compelling in their clarity and immediacy.”

The fact Kok chose to practice art to further medical knowledge and later in life for her own fulfillment is why the artist has remained largely unknown in the Maine art world and beyond ever since she and her husband, Jan, ventured to Maine in the 1960s.

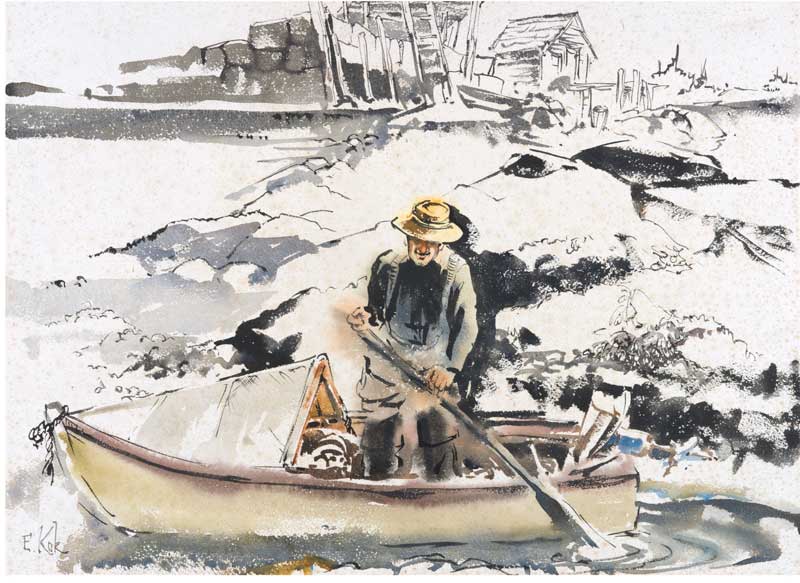

In Stonington, Kok often perched on the shorefront and captured in watercolor and pen and ink clammers and other locals going about their lives.

In Stonington, Kok often perched on the shorefront and captured in watercolor and pen and ink clammers and other locals going about their lives.

There Has to be Magic’s cover shows the artist at work.

Kok’s impulse as a visual artist sprang from her early childhood and ancestors. Her maternal great-grandfather, Simon Wing, was born in a log cabin on Saint Albans Mountain in western Maine’s Somerset County. He became fascinated with daguerreotype—an early form of photography in which images are reproduced on silver-surfaced plates—in his mid-20s and became a professional photographer and innovator whose Wing Multiplier Camera produced 144 tiny images on one tin plate. His subsequent line of cameras are prized collector’s items today.

There Has to be Magic’s cover shows the artist at work.

Kok’s impulse as a visual artist sprang from her early childhood and ancestors. Her maternal great-grandfather, Simon Wing, was born in a log cabin on Saint Albans Mountain in western Maine’s Somerset County. He became fascinated with daguerreotype—an early form of photography in which images are reproduced on silver-surfaced plates—in his mid-20s and became a professional photographer and innovator whose Wing Multiplier Camera produced 144 tiny images on one tin plate. His subsequent line of cameras are prized collector’s items today.

Wing expanded his product line—adding wooden tripods and camera boxes—and moved his business, S. Wing & Co., from Maine to Boston where he opened a factory and photography studio in Charlestown, Massachusetts, and expanded with 31 photo studio franchises and partnerships from Freemont, Ohio, to San Francisco.

Wing became politically active. He opposed slavery and later hired a runaway teen-age slave, Anson Fosky, to caretake his country home west of Boston. He also believed women were entitled to vote under the U.S. Constitution and had other social concerns that led him to found the short-lived U.S. Socialist-Labor Party and run as its first candidate for U.S. President in 1892. He won over 20,000 votes in six states, but lost his bid to Grover Cleveland.

Wing’s daughter Anna became one of America’s first female photographers. She and a partner, Alma Whitney, opened an all-women photography shop in 1900, employing Anna’s daughter and a female friend.

Wing’s son, Harvey—Evelyn’s grandfather—eventually took over S. Wing & Co. A passionate sailor, he and his wife Eva eventually moved to the North Shore town of Revere, Massachusetts, where he acquired the nearby Ocean Pier Boathouse to dock his sloop Magnolia. He later physically moved the rambling, two-story structure and converted it into a home. The Wing boathouse, in The Life of Evelyn Kok, is described as “a happy place where Harvey’s granddaughter, Evelyn, spent her first 18 summers, festive and often filled with friends and neighbors who would gather for lively evenings, singing and playing music.”

Evelyn Kok did her own artwork and taught art and music while working for 30 years as the librarian at the University of Maine at Presque Isle.

Like her aunt Anna, Harvey Wing’s daughter Cora continued the family tradition of bucking convention. Her request for a pocket knife for her 8th birthday proved prophetic. She became a sculptor and was among the first women admitted to the Boston Museum School (now the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University). She also fell in love with a Norwegian immigrant named Anton Olsen, who lacked much formal education, but was a skilled craftsman and loved to sail. He kept his racing sailboat, the Problem, at Wing’s pier.

Evelyn Kok did her own artwork and taught art and music while working for 30 years as the librarian at the University of Maine at Presque Isle.

Like her aunt Anna, Harvey Wing’s daughter Cora continued the family tradition of bucking convention. Her request for a pocket knife for her 8th birthday proved prophetic. She became a sculptor and was among the first women admitted to the Boston Museum School (now the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University). She also fell in love with a Norwegian immigrant named Anton Olsen, who lacked much formal education, but was a skilled craftsman and loved to sail. He kept his racing sailboat, the Problem, at Wing’s pier.

Cora’s father opposed the match. “If you step onto the Problem, we will have a problem!” Harvey Wing declared, warning his daughter. “And you, dear girl, will have to marry that man.”

Cora did just that. A 1923 photo shows her seated, cradling the couple’s bundled newborn daughter, Evelyn, in the Problem’s cockpit. A smiling Anton, with their 3-year-old Louise on his lap, sits at the helm of the craft under sail.

Motherhood did not keep Cora from pursuing art. She whittled an armada of ship models and elaborate dioramas, between parenting and running her family’s household in Watertown, Massachusetts. Boston’s T Wharf inspired Cora’s most ambitious piece, which stands in The Gallery of the Purple Fish. Five feet in length, the diorama shows three-story warehouses flanking the pier. Commercial vessels are tied up or pulling up alongside. The skyline and billowing clouds were painted by daughter Evelyn.

Anton Olsen ran a successful house-painting and interior detailing business. He also carried on his Norwegian ancestors’ specialty of creating tine boxes. A strip of wood is steam-bent and the ends woven together with tree root such as birch. The decorative boxes are then painted in flowing floral and scroll motifs called rosemaling.

Norwegian-born Anton Olson taught his daughter, Evelyn Kok, Norway’s decorative artform of tine boxes.

Norwegian-born Anton Olson taught his daughter, Evelyn Kok, Norway’s decorative artform of tine boxes.

Watching her mother whittle or her father paint a bentwood box, young Evelyn took it all in, teaching herself rosemaling, which she used to embellish musical instruments as well as the tine boxes she and her father made. Fiercely independent, Kok took off after graduating from high school in 1942. She lifted her bicycle aboard a train and eventually biked alone through northern Quebec where she spent the summer painting and living in indigenous Cree communities.

In 1947, Evelyn Kok observed and sketched a live surgical procedure in which thoracic surgeon Dr. Richard Overholt removed cancerous parts of a lung at the New England Deaconess Hospital. Her final drawing was executed on drafting film paper.

In 1947, Evelyn Kok observed and sketched a live surgical procedure in which thoracic surgeon Dr. Richard Overholt removed cancerous parts of a lung at the New England Deaconess Hospital. Her final drawing was executed on drafting film paper.

Graduating in 1946 from Boston’s School of Practical Arts, which later became the Art Institute of Boston, she took a Dutch freighter to Europe where she cycled and hosteled with young aid workers as part of a goodwill mission to provide humanitarian assistance across Europe following World War II. On board the freighter, Kok befriended the ship’s Dutch cook and the two taught each other folk songs while peeling potatoes. One traditional Dutch tune stuck and she would sing it several years later while recounting her postwar hosteling adventures at a Harvard University Outing Club event in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Faltering on Dutch words in the second verse, she heard a voice rise from the back of the hall, singing the missing lyrics. Jan Kok, a Dutch-born Harvard graduate student in math and music, knew the song well from his homeland. Their voices joined and finished the folk song. The impromptu duet sealed their future together.

Jan and Evelyn were married in 1951. A musicologist, educator, and composer, he and Evelyn struck out for Maine’s Aroostook County where he would teach and head the music department while she served as librarian for over three decades at the University of Maine at Presque Isle. She also gave art and music lessons.

The Koks delighted in making music together and with others. They both played many instruments—piano, harp, lute, violin, and drums to name a few—and performed widely as a duo.

Cora Olsen cradles her newborn daughter Evelyn while her husband Anton lets their elder daughter Louise sail the Problem in 1923. Harvey Wing photo courtesy Christina Shipps

Cora Olsen cradles her newborn daughter Evelyn while her husband Anton lets their elder daughter Louise sail the Problem in 1923. Harvey Wing photo courtesy Christina Shipps

The Problem, seen here running wing-on-wing, was kept at a pier in Revere, Massachusetts.

While Presque Isle was home, summers in Stonington enabled Evelyn to get her fix of salt air, and devote herself to the more contemplative practice of drawing and painting. She and Jan usually spent at least a week aboard the Stephen Taber as guests of Captain Ken Barnes and his wife, Ellen. Evelyn took plenty of art supplies and made fanciful potato prints for and with passengers.

The Problem, seen here running wing-on-wing, was kept at a pier in Revere, Massachusetts.

While Presque Isle was home, summers in Stonington enabled Evelyn to get her fix of salt air, and devote herself to the more contemplative practice of drawing and painting. She and Jan usually spent at least a week aboard the Stephen Taber as guests of Captain Ken Barnes and his wife, Ellen. Evelyn took plenty of art supplies and made fanciful potato prints for and with passengers.

Jan and Evelyn also sang for their supper aboard the schooner. With handmade instruments—maybe a dulcimer or mandolin—the Koks sang playful duets that she composed, such as “I Can Sail and You Can Bail” and coaxed the schooner’s crew and passengers to join in.

“My aunt loved the ocean and identified with sailing,” reflects Shipps who remembers Evelyn and Jan sailing around summer afternoons in a little yellow Scaffie, a dinghy-sized sailboat, called Buttercup. Her aunt’s love of schooners “weaves a thread from her grandfather Harvey Wing’s love of sailing and life in his boathouse to her father Anton’s craft, the Problem, and her mother Cora’s sculpted ships.”

In 2013, the Koks received Central Aroostook Chamber of Commerce’s Lifetime Achievement Awards for sharing their love of music far and wide and for her visual art work. Evelyn’s watercolors also grace the Presque Isle Public Library’s Writer’s Room, which was created in her memory.

✮

Letitia Baldwin is a freelance writer who lives in the downeast town of Gouldsboro and Cranberry Isles. She previously worked as the Arts & Leisure Editor at The Ellsworth American and style editor at the Bangor Daily News.

Evelyn Kok was a joyful soul who shared her love of Maine through fine watercolors and whimsical songs.

For More on Evelyn Kok

Evelyn Kok was a joyful soul who shared her love of Maine through fine watercolors and whimsical songs.

For More on Evelyn Kok

Author Donna Marie McNeil’s book There Has to be Magic: The Art of Evelyn Kok and limited-edition prints and greeting cards of the Bookmark Lady’s original pen-and-ink watercolors can be purchased at www.theartofevelynkok.com. For more information, call 207-367-2690 or email info@artekok.com. The Stonington gallery will not be open during 2024. Some of Evelyn Kok’s medical illustrations are on view this summer, June 3 through October, 2024, in the MDI Biological Laboratory’s exhibition, “Art Meets Science,” at 159 Route 3, in the Bar Harbor village of Salisbury Cove.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.