Paul Black

Impressionist

All painting photos courtesy of the Black family

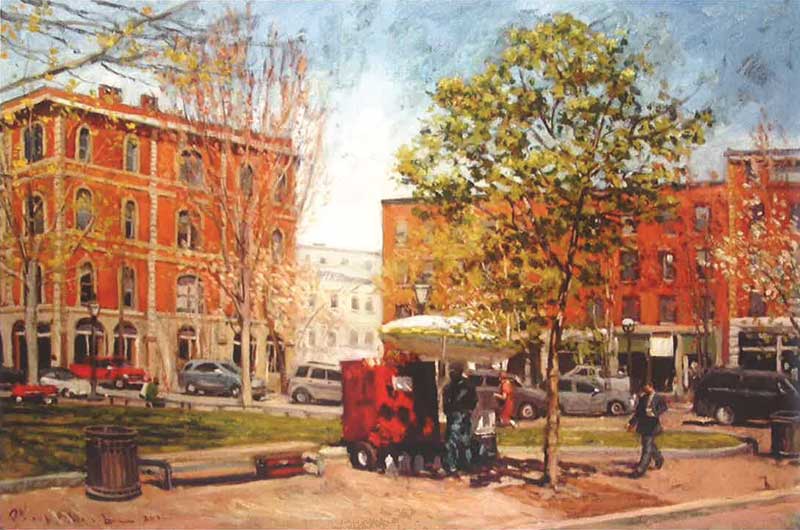

Paul Black’s painting of Tommy’s Park features Mark Gatti’s red hotdog cart, a mainstay of Portland’s Old Port. Tommy’s Park, Middle and Exchange, 2012, oil on canvas, 24 by 36 inches.

Paul Black’s painting of Tommy’s Park features Mark Gatti’s red hotdog cart, a mainstay of Portland’s Old Port. Tommy’s Park, Middle and Exchange, 2012, oil on canvas, 24 by 36 inches.

When Paul Black passed away in 2014, he left an impressive—and Impressionist—legacy of art. Channeling Claude Monet and company, Black transformed the Maine landscape into gorgeous canvases using brisk brushwork. Whether painting Monhegan, greater Portland, Mount Desert Island, Bangor, or other spots, he captured place with a particular poetry.

Black took on each locale with focus and determination. His wife, Irena, recalls the crates of canvases and paintings he would transport to Monhegan each year. He built his own travel boxes for all of his art supplies, she relates, “and the deckhands always laughed when we put those massive crates on the boat.” On island, he would set up a small rental space as his “Monhegan gallery,” a place to paint and show his work. He spent every summer there from 2002 until his death.

Later in life, Black turned his Impressionist eye—and brush—to Monhegan Island subjects. Monhegan Meadow, 2014, oil on canvas, 24 by 36 inches.

Irena and daughter Holly would work around Black’s schedule, popping into his studio/gallery during the day to visit “if he wasn’t out painting on a hike somewhere.” Among Holly’s favorite memories of these Monhegan retreats, writes her mother, was sitting at Lobster Cove with her father after a massive storm. “It was a beautiful day…and the waves were huge, and we all went back and forth all day to watch them crash along the shore by the Wyeths’ house.”

Later in life, Black turned his Impressionist eye—and brush—to Monhegan Island subjects. Monhegan Meadow, 2014, oil on canvas, 24 by 36 inches.

Irena and daughter Holly would work around Black’s schedule, popping into his studio/gallery during the day to visit “if he wasn’t out painting on a hike somewhere.” Among Holly’s favorite memories of these Monhegan retreats, writes her mother, was sitting at Lobster Cove with her father after a massive storm. “It was a beautiful day…and the waves were huge, and we all went back and forth all day to watch them crash along the shore by the Wyeths’ house.”

Black’s Monhegan paintings include many classic motifs: the island of Manana, the Island Inn, the wharf, rooftop views of the harbor. A painting of a meadow with a greenhouse testifies to his ability to capture light: the canvas is alive with sun and shadow. His brother Peter remembers talking to him about the painting, “about the energetic, gestural brushwork and pure, saturated color he was using, channeling Van Gogh.”

Black offers a wide-angle view of this cobble-stoned square on Fore Street in Portland. Portland Old Port, 2013, oil on canvas, 20 by 30 inches.

The painter is perhaps best known for his Portland pictures. Black captured the city by the sea in all seasons, including the depths of winter. Speaking about a particular snowy view of Exchange Street, he told Portland Monthly editor Colin Sargent that what gave the scene warmth were “the streetlights, the windows on the stores, and the figures, some of which are modeled on my own memories—my wife, my daughter.” He also noted how he tended not to letter the signs on shops because “businesses change.”

Black offers a wide-angle view of this cobble-stoned square on Fore Street in Portland. Portland Old Port, 2013, oil on canvas, 20 by 30 inches.

The painter is perhaps best known for his Portland pictures. Black captured the city by the sea in all seasons, including the depths of winter. Speaking about a particular snowy view of Exchange Street, he told Portland Monthly editor Colin Sargent that what gave the scene warmth were “the streetlights, the windows on the stores, and the figures, some of which are modeled on my own memories—my wife, my daughter.” He also noted how he tended not to letter the signs on shops because “businesses change.”

Black’s Portland subjects included Tommy’s Park on Middle Street and images of the Old Port’s cobblestone roadways rendered in his signature Impressionist style. In one canvas, a fleet of 420-class sailing dinghies makes its way across Casco Bay in front of Portland House and the Eastern Prom, their sails catching the wind.

Meeting Black at one of his shows at the Fore Street Gallery in Portland, painter David Little remembers asking the artist how he was able to create “such unified moods” in his paintings, “especially the overcast, stormy coastal scenes and the warm, snowy winter scenes of the Old Port.” Black had studied the different skies in the paintings of Monet, Camille Pissarro, and John Constable, and admitted that when he was having trouble unifying a painting, he would utilize the mood and brushwork of one of those painters.

Black’s paintings of snowy streets in Portland are among his most coveted. Boothby Square, 2014, oil on canvas, 24 by 48 inches.

Rita Redfield, who showed Black’s work at her self-named gallery in Northeast Harbor every summer from about 1982 to 2017, recalls that the Asticou Azalea Garden was one of his favorite subjects. “From year to year, through his paintings,” she notes, “one could see the change in the Alberta spruce at the end of the pond.”

Black’s paintings of snowy streets in Portland are among his most coveted. Boothby Square, 2014, oil on canvas, 24 by 48 inches.

Rita Redfield, who showed Black’s work at her self-named gallery in Northeast Harbor every summer from about 1982 to 2017, recalls that the Asticou Azalea Garden was one of his favorite subjects. “From year to year, through his paintings,” she notes, “one could see the change in the Alberta spruce at the end of the pond.”

Black’s work received favorable critical notice over the years. “Under Black’s hand,” wrote Donna Gold in Maine Times, “Bangor becomes Paris: romantic, soft, full of secrets.” In a review in the Maine Sunday Telegram, critic Dan Kany noted, “He is not afraid to charm, and he has the chops to do it.”

Charming, yes, but Black’s paintings also represent an extension of the formidable line of Impressionist painters who have found inspiration in Maine, among them Childe Hassam, Frank Benson, Willard Metcalf, Carroll Tyson, and Edward Redfield. They, too, drew on European examples in responding to the landscape.

Over the years, Black developed a devoted following. The “idyllic quality” of his paintings, as Bangor Daily News art writer Alicia Anstead described them in a 1999 feature, attracted collectors—and Shipyard Brewing Company, which printed his paintings on the packaging for two of its beers. The 10th anniversary of his passing seems a fitting time to revisit Black’s life and work.

Black painted the Asticou Azalea Garden in Northeast Harbor many times, favoring this view of an Alberta spruce. Asticou Garden, 1987, oil on canvas, 40 by 38 inches.

Black painted the Asticou Azalea Garden in Northeast Harbor many times, favoring this view of an Alberta spruce. Asticou Garden, 1987, oil on canvas, 40 by 38 inches.

Paul Francis Black was born in Bangor on the last day of 1951, the son of John and Marcadais Black. He played Little League baseball and attended local schools. At Bangor High School, his brother Peter recounts, “he filled out and grew a beard” and played Bill Sikes, the villain, in Oliver!

Black showed talent in drawing from an early age. “The teachers were always amazed because other kids were just drawing sticks,” he told Anstead. “I wasn’t extraordinary, but I was good enough to draw praise, and every kid wants that.”

Black’s sister, Mitzi, recalls sitting at the dining room table with him drawing pictures. “He could sketch anything from landscapes to cartoon characters!” He taught her how to draw Fred Flintstone, “and to this day,” she writes, “it is my go-to when asked to draw something.”

Black received artistic support throughout his school years. Ronald Sands (1936-1991) and Palmer Libby (1928-2005) offered encouragement at, respectively, Fifth Street Junior High and Bangor High. He also took inspiration from the work of Maine painters such as Waldo Peirce and William Moise.

Later, at the University of Maine in Orono, Vincent Hartgen and Michael Lewis proved to be important guides, both of them legends in the annals of that institution’s art department. Black earned a BA in art in 1977.

Among early work is a small printed history of the peavey cant-dog, a logger’s tool, illustrated with Black’s woodcuts. He also made a series of etchings inspired by Charles Eliot’s classic Maine coast biography John Gilley of Baker’s Island.

When he wasn’t painting, Black played bass guitar with Randy Hawkes and the Overtones. He loved rock ‘n’ roll and painted portraits of Jimi Hendrix, Ginger Baker, the Beatles, and other musical heroes. He never lost his love of music and continued to play throughout his life.

A fleet of 420-class sailing dinghies finds the wind on Casco Bay. Regatta, Eastern Prom, 2012, oil on canvas, 24 by 36 inches.

Intending to become a full-time painter, Black moved to Seal Harbor on Mount Desert Island in 1980. His early paintings were “very crude,” he told Anstead in the 1999 interview, but he realized they represented “little pieces of nature.” Suddenly, he recounted, “the world changed and everything looked like a painting to me.”

A fleet of 420-class sailing dinghies finds the wind on Casco Bay. Regatta, Eastern Prom, 2012, oil on canvas, 24 by 36 inches.

Intending to become a full-time painter, Black moved to Seal Harbor on Mount Desert Island in 1980. His early paintings were “very crude,” he told Anstead in the 1999 interview, but he realized they represented “little pieces of nature.” Suddenly, he recounted, “the world changed and everything looked like a painting to me.”

Black met Irena Holtz in 1996 and they married. Daughter Holly arrived the following year. The family spent all of its years in South Portland where the painter established his studio and where, Irena says, his art career “really took off.”

While Black’s principal passion lay in painting, he maintained other infatuations. When Holly began playing violin at age 5, he became an aficionado of that stringed instrument. He took lessons with her and became interested in how violins were made. “He started buying old beat-up violins and restoring them,” Irena recounts, “and either giving them or selling them at low cost to students at the Portland Conservatory of Music who were in need of instruments.” In a hilarious account of his obsession with purchasing violins on eBay, Black offered various excuses for why long cardboard boxes regularly appeared on his porch.

Hugh, Black’s older brother, praised his skill around cars. In a reminiscence sent to Irena, he remembered Paul removing a transmission from an “abandoned old Saab” on Cape Cod and installing it in his own car—“and it lasted for a long time.”

Irena provides further testimony to her husband’s skills. “Paul was great with his hands,” she says. He built his own studio and made furniture for their house, and “just generally would rather build things instead of purchase them.” As he enjoyed painting sailboats, “which he did often,” she notes, he decided to build a boat from scratch. The Holly B., named for his daughter, was the result.

Black donated paintings to a wide range of nonprofits, including North Yarmouth Academy, the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project, the Children’s Museum of Maine, American Cancer Society, the Great Cranberry Historical Society, and the Cape Elizabeth Land Trust. At one point, he created limited edition prints of his painting of the Cushing’s Point House to help the South Portland Historical Society purchase the historic building.

Clockwise from upper left: Paul Black’s studio in South Portland; working on his boat, the Holly B.; a cluttered music stand; and playing guitar—he was a lifelong musician.

Clockwise from upper left: Paul Black’s studio in South Portland; working on his boat, the Holly B.; a cluttered music stand; and playing guitar—he was a lifelong musician.

“It is my hope,” Black once stated, “that in these days of fiscal austerity…the importance of art is not overlooked when dividing limited resources for education.” To that end, his obituary suggested that in lieu of flowers, donations be made “to the art and music departments or the girls’ basketball program at South Portland High School.” That’s the kind of artist he was, kind and generous—and grateful to the individuals who saw his talent early on and encouraged him to pursue a life in art.

✮

Carl Little lives and writes on Mount Desert Island. His latest book, in collaboration with his brother, David Little, is Art of Penobscot Bay (Islandport Press).

Paul Black’s work can be seen at paulblack.com. He is also represented by the Lupine Gallery on Monhegan. The Healing Arts Commission at St. Joseph Hospital in Bangor will be featuring Black’s work at 900 Broadway, from June 27 to September 28, 2025.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.