Dorothy, Oh Dorothy

Images courtesy Robert Beck

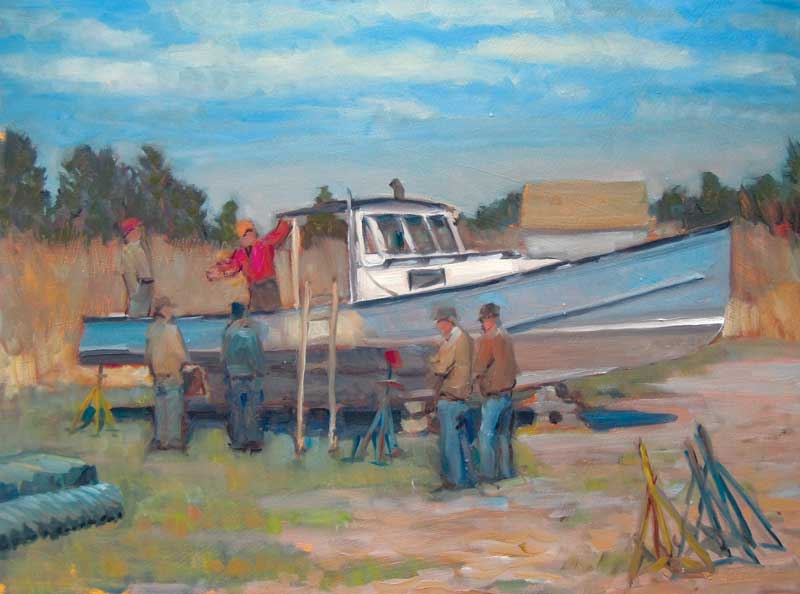

Alley Bay (12 x 16 inches) portrays a breezy spring day at Alley Bay on Beals Island, Maine, as preparations are made for the lobster season. All the paintings for this story are oil on panel.

Alley Bay (12 x 16 inches) portrays a breezy spring day at Alley Bay on Beals Island, Maine, as preparations are made for the lobster season. All the paintings for this story are oil on panel.

How, after all these years, can I harbor an irrepressible longing for a boat that I never owned or even sailed on?

I learned a lesson about these things a long time ago. A woman broke up with me, and I was deeply wounded. Whenever a friend asked if I knew how she was doing, it was a knife to the heart. Many years later, when I was in another relationship—a better one by all measure—someone referred to that first woman, and I felt the stab again. But this time, it confused me. I didn’t miss her. I was doing fine. So why the pain? I realized it wasn’t the long gotten-over relationship I was reacting to; it was the memory of the heartache. I was reliving how that felt.

This happens to me when I think about the Dorothy, the 38-foot downeaster with a built-up cedar-plank hull and single diesel that was almost mine.

My attraction to boats developed in my 40s. I’m an artist, and I was drawn to New England for the subject matter. In time, I found a place in Maine, about an hour from Canada, where I could focus on life in a rural maritime community. For more than a decade, I painted boatbuilders, lobstermen, and people of all walks in the remote fishing village of Jonesport. In time, the townsfolk accepted me, doors opened, and opportunities arose. I went out on lobsterboats, watched them get built, and developed a reverence for the high level of craftsmanship involved in wooden boatbuilding. Some of them were works of art.

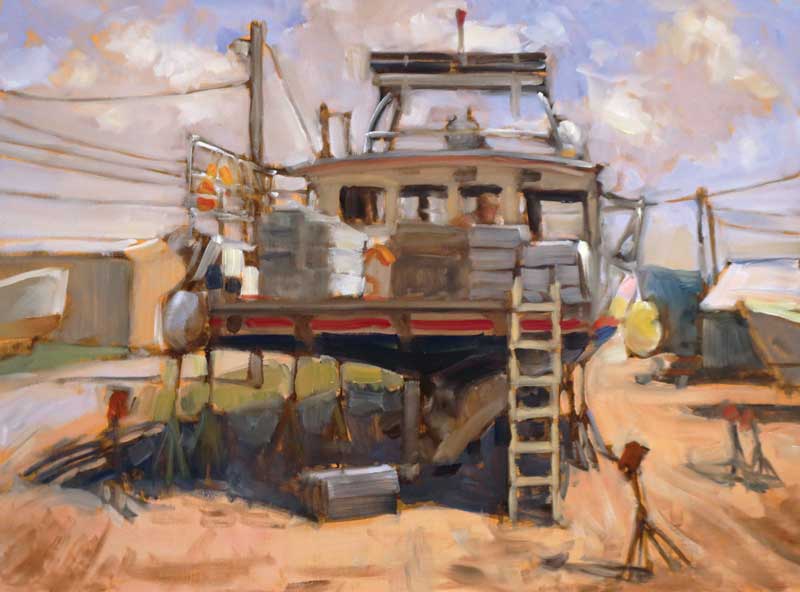

A 28-foot wooden lobsterboat sits on stands outside the author’s cabin in Jonesport, Maine, in Blue Angel (12 x 16 inches).

A 28-foot wooden lobsterboat sits on stands outside the author’s cabin in Jonesport, Maine, in Blue Angel (12 x 16 inches).

It’s hard to pinpoint where it got obsessive—maybe with Blue Angel. The cabin I rented in Jonesport was at the shipyard on Sawyer Cove, and boats were put up on stands outside my door. Blue Angel was one of those classic lobsterboats with exquisite lines. Not big or fancy, but sweet. The owner decided the bill for repairs and storage was more than the boat was worth to him, and he walked away from it. By law, the shipyard could put it up for auction after a remarkably short time, but it sat there for a couple of years.

I had my morning coffee outside with Blue Angel, feeling the breeze and listening to the gulls. I painted her a couple of times. I thought we made a good pair. The shipyard finally held the auction. By then, I had spent a lot of time fantasizing about fixing her up and cruising the reach and bays. I asked what she might go for and was told possibly as little as a few hundred dollars, but the truth was that unless I did the wood repairs and fixed the engine myself, it would be a costly proposition.

Jonesport is 11 hours away from where I live and I was only there a handful of weeks every year. I’m not wealthy. It made no sense. A couple of youngsters got Blue Angel for next to nothing and hauled her away. They would do the work, get her seaworthy, and tend lobster traps, which is how it goes in Maine. I wondered if I had missed my chance.

I have a close friendship with the shipyard’s owner, sharing a common appreciation for good-looking boats. He brokers boat sales and keeps an eye on the market. I don’t remember which one of us found the Dorothy for sale a half-hour down the coast. There was a lot that was right about her. Much more than Blue Angel. The Dorothy had a lovely sheer, but the topside proportions were unusual. The house roof was low, and the cabin was tall, which made the two-pane windshield appear to squint into the distance. The Dorothy was set up for day cruising but cut a no-nonsense working-boat figure. She could have been out of the 1950s. That’s fine; so am I. The price was right.

A meager crowd shows up as Blue Angel goes under the gavel in Boat Auction (12 x 16 inches).

A meager crowd shows up as Blue Angel goes under the gavel in Boat Auction (12 x 16 inches).

Buying a boat is like buying a horse; it’s best to have someone who knows what they are looking at give it a good once-over. When you are serious, you hire somebody to do an official survey, but my friend knew boats, and he knew me, and could get us past the first step. We decided to drive down and see what she was like.

The Dorothy was still wrapped for storage when we arrived, which was annoying. They knew we were coming to inspect the boat for possible purchase, yet we had to climb a ladder between the hull and tarps to reach the deck with flashlights. It was a sunny summer day, and it was unpleasantly hot and stuffy under there. I expected the boat to be tired, worn, and dirty, but the pools of light revealed a tidy and hallowed vessel.

If boats ever come with ghosts, this would be one. The Dorothy had been hand-built to satisfy somebody’s unique purposes and desires, which it did for many years. There was nothing fancy about the design, but everything was well-considered and certainly cared for. She had been put up clean and ready for the next season, which didn’t come.

The helm controls—wheel, throttle, compass, and clock—were basic but good quality; they were everything you would need to run around the harbor or out to an island. We lifted the engine case in the center of the deck, and it all looked in order, just old. It was reportedly in running condition, which would be easy to confirm before a sale.

Willis Beal prepares traps in his boatbuilding shop in Willis Beal (16 x 20 inches). The artist had Beal sign the painting in the lower left corner.

Willis Beal prepares traps in his boatbuilding shop in Willis Beal (16 x 20 inches). The artist had Beal sign the painting in the lower left corner.

The low roof on the house was a puzzle. I had to duck. I was told that the boat was built for a woman who owned and sailed it her whole life, but that’s no reason for a low ceiling. And it was the opposite below.

Down a short set of steps forward, the cabin was comfortable and clean. The extra headroom meant I could stand up, which is unusual in most classic lobsterboats. The cabinetry was plywood with pine trim—well-made, with solid, vintage hardware and a smooth varnish gone to dark amber. An area to the left held a vintage two-burner marine gas stove, a sink surrounded by pink pearl Formica, and plenty of storage. A roll of paper towels hung in the holder, and a kettle rested on the grate. There was no attempt at fancy style or decoration. The space had a practical, mid-century hunting-cabin esthetic. To the right was an adequate head, and a V-berth was tucked in the bow. You could live a hot-meal existence for as long as your fresh water held out. There wasn’t any rot, rust, or corrosion. The Dorothy was more than a half-century old, yet looked like you could sweep her out and launch tomorrow.

There was no shower or refrigerator. Along the upper reaches of the Maine coast, you are less likely to find places to dock, clean up, and resupply, but it wasn’t my plan to go on long trips, and I didn’t consider those things a necessity. The truth is, I didn’t know what my plan was. It was a compulsion, or maybe a crush. I could see myself sitting on her deck with that cup of coffee, feeling that breeze, listening to those gulls.

I’d have to raise the house’s ceiling and probably replace the electronics, but the work list was short. The surprises were all good. Did I mention my mother’s name was Dorothy? We decided my shipyard friend would return to check the hull inside and out after the yard had unwrapped the boat.

I had to return to Pennsylvania. All I thought about was the Dorothy. I did some drawings of what she would look like with 6 inches added to the house. She was even better like that—less squint, more Garbo. It wasn’t clear how long-distance boat ownership would fit into my crowded and prescribed life, but what I had seen was too right to turn away.

Winter’s Return (24 x 32 inches) is a studio painting, with the artist using the Moosebec Reach, an old Novi dragger, and some inhospitable weather as subjects.

Winter’s Return (24 x 32 inches) is a studio painting, with the artist using the Moosebec Reach, an old Novi dragger, and some inhospitable weather as subjects.

Until I had to. My friend called me and said there was a big problem. The Dorothy had been out of the water for a while, and the hull was twisted from how she sat on the supports. Planks had unfastened and pulled away. You couldn’t put her in the water without a major refastening and possibly much more. I didn’t have the wallet for that.

It was a heartbreak. In the fog of infatuation, I had been lifted by great possibilities and new horizons, and the reality dropped me flat. I come across the photos now and then and still feel the dispiritedness wash through me. How it would have unfolded if the hull had been fine and I’d bought the boat is anybody’s guess. There would have been less room for the things that have happened since, which have been pretty great. There is no what if, just what was, and no regrets.

I subscribe to a website for people who love classic boats. It has stories, photos, boats for sale, and excellent instructional videos. Earlier this year, I received an email letting me know that the site has “40 Maintenance Videos—Paint + Varnish + Epoxy” for “boat maintenance season.”

Forty maintenance videos. What are you doing the next eight or 10 weekends? Anybody who owns a boat groans when thinking about the chores and the cost. I don’t have to deal with that, just the irrepressible longing as the Dorothy rocks gently underfoot on Sawyer Cove in my imagination.

✮

Robert Beck is painter and writer who splits time between Pennyslvania, Maine, and Manhattan. Visit robertbeck.net to see more.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.