Beyond Backyard Birdwatching

There's more to birding than just looking at birds. It's all about appreciation, and understanding.

Photographs by Janet Mendelsohn

Will they laugh at my wimpy binoculars? Will I spot the right bird or pick out the right song from among the many? I should know more. After a lifetime of backyard birdwatching, I’m finally… finally… taking the plunge. Today I’m joining a York County Audubon bird walk.

Dave Doubleday, who leads most of the YCA Wednesday walks, assured me that I won’t be the only beginner, that “we’re all novices sometimes.” Still, I don’t want to seem like a dodo. For anyone with an interest, Dave sends weekly e-mails year-round with information on where and when to meet, and what to expect, and a list of birds spotted during the previous outing. Destinations change weekly; they follow the birds. From five to fifteen people might show up. It’s time to stretch my wings.

APRIL 25, 7:00 a.m.

A wild turkey skitters by as I drive into Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve at Laudholm Farm. At least I can identify ONE bird. But even if I don’t see another, this is a beautiful place. Some 2,250 acres of open fields, woodland, salt marsh, and shoreline are devoted to protecting and restoring coastal ecosystems along the Gulf of Maine.

Research, education, and stewardship activities are headquartered at Laudholm Farm, a National Historic Landmark. That’s where I’m meeting the group.

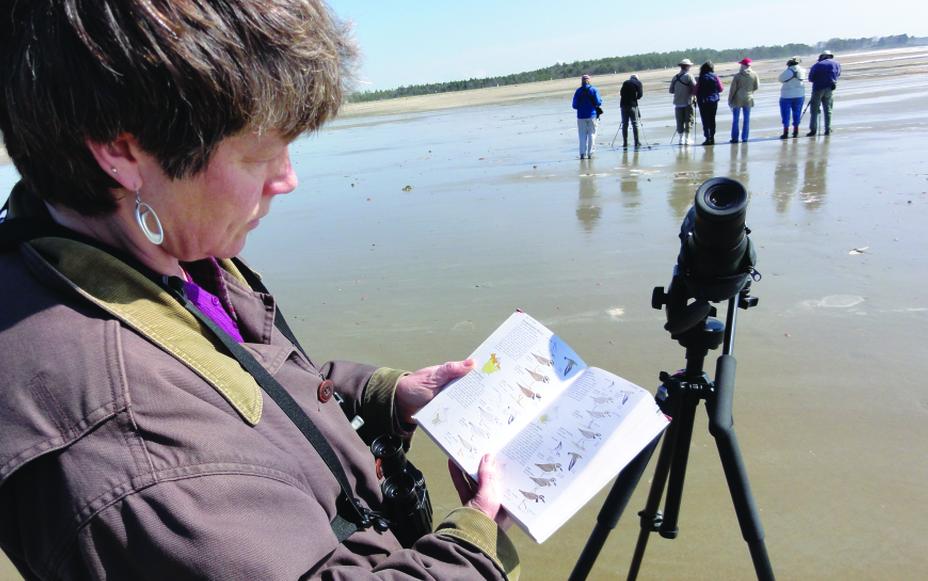

The buildings are egg-yolk-yellow; there are no farm animals. Outside the former dairy barn, seven men and six women, who look to be in their fifties to seventies, are chatting amiably. What I notice first are their binoculars. Mine are, indeed, laughable by comparison. Then I see several tall, slim tripods topped with what looks to be hefty professional photography equipment. I soon learn that these are not cameras but “spotting scopes” that are used to zoom in for National Geographic-style close-ups of birds.

Spotting scopes and fancy binoculars are optional for beginners.

Spotting scopes and fancy binoculars are optional for beginners.

Apparently the birder dress code favors hiking boots and beige hiking pants. I’m wearing sneakers and jeans. Dave had warned me to avoid bright colors, which can distract the birds. At least my sea-green fleece vest and black windbreaker were smart choices. There’s a chill coastal breeze.

This newbie is greeted warmly by all. Nonetheless, still nervous, on a quick, last-minute pit stop, I realize I’m exiting not the ladies’ room, but the men’s. Embarrassed but luckily alone.

And then, it’s all good. The sky is clear, cloudless. The air is sweetly scented, a seasonal blend of seacoast and moist spring earth. As my Mom would say, it’s a glorious day. Introductions begin.

We are a mix of novices and longtime birders, mostly from Portland, Kennebunk, Parsonsfield, and Wells. We stop when someone hears a meadowlark, then Dave spots an osprey overhead. “Notice its white head and black knees,” he says. Everyone turns.

Crossing a meadow edged by low bush and tall trees, Dave stops us a few yards into the trail. That’s the bubbly, squeaky song of a house finch, he says, pointing to a distant tree. That’s a mockingbird in the grass, he says. All I see are brown, small birds flitting about. Which are which? I don’t ask. Birdwatching is about much more than spotting birds.

Birdwatching is about much more than spotting birds.

We stroll on, talking softly while pausing to listen to gulls, goldfinches, and a blue jay—another that I know!—calling their kin. Dave points out a turkey vulture flying straight toward us. Scopes and binoculars zero in. “Notice its dihedral shape,” he says. “The way it holds its shape is key to identification.” Field guides emerge from pockets so we can compare the vulture to the hawks.

“Drink your tea, drink your tea,” Dave mimics, trilling up at the end of the call. He has spotted an Eastern Towhee, a beautiful reddish, black-and-white bird. I’m invited to look through a scope. The bird is dazzling!

Now that I know where to look, my binoculars aren’t as bad as I first thought. I’m watching the singing Towhee’s throat quiver when Dave says, “He’s probably telling another bird, ‘This is my turf; don’t come too close.’”

We’ve barely begun but, by my standards, the day is already a success. I can identify four.

At a salt marsh viewing station where the wetlands boardwalk ends I’m again invited to view shorebirds through a powerful scope. I ponder this generosity on the walk’s next leg, lingering too long on the marsh boardwalk, distracted by tiny white wildflowers, robust leafy plants (skunk cabbage?), and thumb-size, periwinkle-blue butterflies. Jogging to catch the group, I take a stab at the bird call that has caught their attention. Wrong.

“Don’t be intimidated,” says birder Bob Watson. “We all make mistakes. Even though some of these people have years of experience birding, there are always alternatives. That could have been a catbird mimicking something else. That’s why we always have field guides.”

Dave is not my only teacher.

The beach here reminds me of the Hamptons, or Cape Cod minus dunes. A few vacation homes front a long, inviting expanse of clean sand. Two deer sprint through the grass behind us as we walk along the shore, looking for piping plovers. There they are, where the tide runs out in ribbons, shimmering.

Endangered royalty, piping plovers are protected by law, which means we are forbidden to get close. But three are standing in the receding water, clearly visible even to my naked eye. Dave points to black rocks in a nearby gully where there are black-bellied plovers, bigger than their brethren. We compare the birds’ shape, colors, and size.

“The joy for me is that you don’t have to go far or spend a lot to go birding,” Lois Winter, a conservation biologist from Portland, says when we finally move on. “It’s an excuse to go outdoors. You can easily do it throughout your lifetime and never stop learning. First you might be attracted by birds’ behaviors. When you can’t see the birds because of the trees, you get into their songs. Over time you see how their colors change with the seasons, who flies off and who sticks around. You want to know why they do what they do. Then you might get interested in habitat and what we are doing to the environment, how that affects them.”

When Lois claims it is an inexpensive hobby, my face must read “skeptic.”

“All you need is binoculars and a guide book,” she insists. “If you get more into it, buy a spotting scope and tripod, and you’re set for life.” She recently splurged on an ultra-lightweight titanium tripod, which, at her prompting, I lift. Nice. Easy to maneuver and carry. I want one. (Dream on.)

Back near the barn, we all watch a juvenile red-tailed hawk, sunning on the roof of a shed.

For one entire morning, I’ve forgotten everything but watching birds with these friendly folks who generously share what they see and know. I’m calm. I’m relaxed. I’ll do this again.

The next week, Dave’s e-mail reports that in two-and-a-half hours we covered two miles and saw or heard 40 species of birds.

You don't have to go far, you get to be outdoors, and you can do it throughout your lifetime.

You don't have to go far, you get to be outdoors, and you can do it throughout your lifetime.

JUNE 8, 8 a.m.

A flash of bright blue, smaller than a jay, just flew behind a large oak. My first bluebird sighting since I was a kid? I’ve heard they’re around here but didn’t see enough of the bird to check my field guide. This morning, 15 people, most self-declared beginners, met at Hamilton House (circa 1785), a Historic New England property in South Berwick. One is a young boy with his mom. It seems he’s been birding before. My husband, Bob, is trying it for the first time. We all smile at each other, waiting to begin, but the whole group is quiet. Now that I’m past beginners’ anxiety, I recognize it.

Scott Richardson works at Wells Reserve but volunteered to lead this York County Audubon Saturday walk in a different venue to see birds in varied terrain. The property sits on a bluff overlooking the Salmon Falls River, beside Vaughan Woods Memorial State Park. The weather again is perfect.

Starting out, we cut through a meadow, almost immediately seeing several birds flying low in undulating circles. Their bubbling song is “R2D2, R2D2,” or “bob-o-link, bob-o-link,” depending on whose interpretation you prefer. Scott says the bobolinks’ behavior indicates that they are carrying food back to youngsters in nests hidden in tall grass, wet with overnight rain. He tells us what to look for. I see a white stripe on a male’s black back and sandy feathers at the back of the head.

Full sun spotlights a vivid orange Baltimore oriole midway up a nearby tree. The oriole sits still long enough for even the newest novices to focus their binoculars. “They’re like robins on steroids,” whispers Bob aptly. Meanwhile, a plump yellow warbler sings swiftly, repeatedly—“I’m so sweet, I’m so sweet”—while an equally repetitive red-eyed vireo chirps, “Look up!... See me!...Over here.” Bob and I lock eyes and nod. We’re all too familiar with hearing that one at dawn.

We pick up the “keer-ka-lee, keer-ka-lee” of a male red-winged blackbird as he dashes to safety in the trees. Bob says what I’m thinking: “We’ve seen many red-winged blackbirds from here to Ohio, but that’s a wider, brighter red than I’ve ever seen before.” Scott explains that males have these bolder “epaulets” to call attention to themselves during breeding season.

A turkey vulture flies over the tree where the red-winged blackbirds just landed. Two of the smaller birds attack, circling, lunging, harassing the predator until he flies off. Can a turkey vulture feel humiliation? Will this one plot revenge?

“We think of all these as ‘our’ birds,” says Scott, “but they spend two-thirds of their lives elsewhere. If the climate or habitat changes in South or Central America, we may not see as many varieties here as in past years. That’s what may have happened to some warblers and thrushes that used to be so common in Maine but aren’t any more.”

After our expedition, Scott reports that we encountered 34 species, including “my” bluebird.

JULY 15

Yesterday I asked Siri, Apple’s iPhone know-it-all, to play a chickadee’s song. She listed restaurants that serve chicken, so I downloaded iBird, a terrific app that several of the longtime hobbyists were using in the field. At the moment I’m listening to an author on National Public Radio discuss bird behavior. I’m finding this stuff everywhere.

AUGUST 8, 8:30 a.m.

“Look closely,” Dave Doubleday says, “then take out your guide book and see which has the blue bill, which has yellow.”

I’ve just caught up with the group, having misread the directions to our meeting spot on the Eastern Trail at Scarborough Marsh. Dave is answering such questions as, “How do you know it’s a black duck?”

“Black wings,” he says, “but it might have white underneath, because mallards will hybridize with anything that gets close to them.”

Instead of looking at mallards, I’m intently admiring another beautiful place I most likely would never have seen if not for these bird walks. It’s summer, but for shorebirds the fall migration is under way.

“Swallows migrating will spend every available moment catching insects here,” Dave says. “The young will build up their wing power until the frost, when you’ll see them huddled on the telephone wires, then flying south.”

Lois and I linger. Cyclists and walkers pass us. A snowy egret appears. Seen through a spotting scope, the bird’s feet are surprising: They’re very bright yellow.

We catch up to the rest of our group. They report that we have missed a spider that had caught a butterfly and was wrapping it up for a future meal. This much I’ve learned—these walks are about much more than spotting birds. They’re about making time to look closer at nature’s many wonders.

Birding Field Guides

Traditionally, birders refer to their field guides by “family” name—Peterson, Sibley, National Geographic, Golden, etc. Top contenders include:

- Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America by Roger Tory Peterson (Houghton Mifflin)

- The Sibley Guide to Birds of Eastern North America by David Allen Silbey (Knopf)

- National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America by Jon L. Dunn and Jonathan Alderfer (National Geographic)

- The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America by Donald and Lillian Stokes (Little Brown)

- Birds of North America: A Golden Guide by Ira N. Gabrielson and Herbert S. Zim, revised by Chandler S. Robbins (St. Martin’s Press)

Smart-phone apps, such as iBird, are great new tools for quick searches, including by song, on the trails or in the backyard.

Birding Resources

The Maine Birding Trail, opened in 2009, was spearheaded by Bob Duchesne, a Maine State Representative and avid birder. His Maine Birding Trail: The Official Guide is available at www.mainebirdingtrail.com or as a 272-page softcover book with maps from Down East Books for $15.95. An abridged version is free from the Maine Office of Tourism: visitmaine.com.

Other resources

- Maine Audubon

- York County Audubon

- Maine Dept. of Conservation, Bureau of Parks and Lands

- Maine Dept. of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife

- Maine’s National Wildlife Refuges

Contributing Editor Janet Mendelsohn is the author of Maine’s Museums: Art, Oddities & Artifacts (Countryman Press, 2011).

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.