Art Flotilla

Celeste Roberge's seaweed boats float the imagination

Natural historians of an earlier age studied elements of their environment, noticed patterns, and made comparisons to reach scientific conclusions. Celeste Roberge works much the same way; however, she turns her observations into art.

Most recently those observations have involved seaweed.

During a visit to the south shore of Nova Scotia in the fall of 2008, Roberge found a type of seaweed, Agarum clathratum, that interested her. Taken by its distinctive perforations, she gathered some specimens from the beach and brought them home to study.

Roberge is a well-known sculptor whose work can be found in major collections across the country. A Biddeford native, she has explored the world, mainly northern climes, looking for inspiration in the environment. When she finds it, there is no telling how it will eventually manifest itself in her art, which, while conceptual, also is tangible, engaging and provocative.

Roberge was intrigued with the idea of making a seaweed boat. She made this sea lace boat from dried kelp. Photo courtesy of Celeste Roberge

Roberge was intrigued with the idea of making a seaweed boat. She made this sea lace boat from dried kelp. Photo courtesy of Celeste Roberge

When she returned to Nova Scotia the next year for a Maine College of Art residency at Baie Sainte-Marie, Roberge went back to the beach, but could not find any more kelp. So she did further research and learned that this type of seaweed, which grows deep in the North Atlantic, only appears on the shore after a storm has torn it from the ocean floor. Her visit the year before had followed on the heels of Hurricane Kyle. Roberge asked a friend to call her after the next hurricane. This time, she once again found the kelp.

In the course of her research, Roberge consulted with Jessica Muhlin, associate professor of marine biology at the Corning School of Ocean Studies at Maine Maritime Academy in Castine. Muhlin explained that the holes in the seaweed’s blades are thought to be an adaptation that de- creases the influence of high water motion. These perforations have inspired evocative names for the species, including sea colander and sieve kelp.

The artist kneels among boats she made from cast brass, cast iron, and enamel during a residency at the Kohler Arts Center in Wisconsin. Each boat measures 15” x 16” x 43”. Created in Arts/industry, a residency program of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center that takes place at Kohler Co.

The artist kneels among boats she made from cast brass, cast iron, and enamel during a residency at the Kohler Arts Center in Wisconsin. Each boat measures 15” x 16” x 43”. Created in Arts/industry, a residency program of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center that takes place at Kohler Co.

As in previous projects, Roberge set about exploring the seaweed as art. “How can I take it and keep its power?” she asked herself. And how could she transform that power into a work of art without altering it too much?

One idea involved boats. As she explained in the catalogue for the landmark “Maine Women Pioneers III” exhibition at the University of New England’s Portland Art Gallery last year: “After observing gatherers of seaweed along the Nova Scotia shores in their flat-bottomed boats laden with rockweed, I thought, ‘Why not a boat, a seaweed boat; better yet, a seaweed boat that

cannot float.’”

First Roberge had to figure out how to dry the kelp without it shriveling up. “It was like a laboratory set-up,” she recalled, describing using sand, then rice, then beans to absorb the seaweed’s moisture. The sand stuck to the seaweed; while the rice absorbed the water, it also got soft and sticky and made a mess. Dried beans proved to be the ideal solution, allowing just enough air to circulate without absorbing too much wetness. “Kind of like Goldilocks’ description of the beds,” Roberge said, “Too soft. Too hard. Just right.”

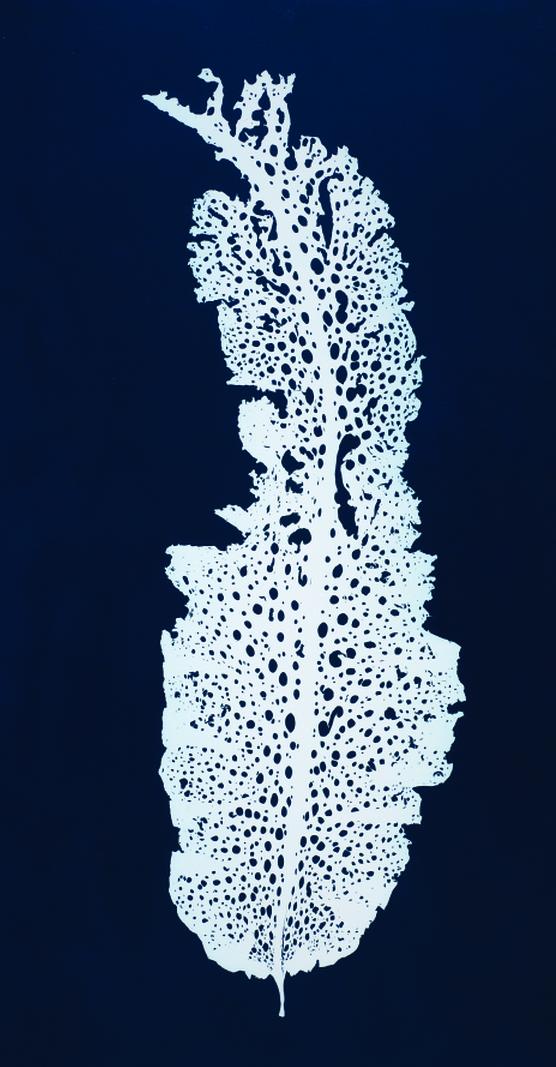

Roberge worked with a master printmaker to create contemporary cyanotypes of Desmarestia aculeata seaweed (below) and Agarum clathratum (above)—the same type of kelp she used to make some of the early boats. Photos by Robert Diamante (2)

Once she had dried the seaweed, Roberge used it to make a series of sea lace boats, vessels so delicate they required magnets to keep them in place when they were shown in Florida earlier this year. A group of them made up the installation “Marina” in her exhibition “Ocean Floors: Works by Celeste Roberge” at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum at Flagler College in St. Augustine. Roberge went on to fabricate the seaweed boats in different metals, playing with variations on their shape.

Roberge worked with a master printmaker to create contemporary cyanotypes of Desmarestia aculeata seaweed (below) and Agarum clathratum (above)—the same type of kelp she used to make some of the early boats. Photos by Robert Diamante (2)

Once she had dried the seaweed, Roberge used it to make a series of sea lace boats, vessels so delicate they required magnets to keep them in place when they were shown in Florida earlier this year. A group of them made up the installation “Marina” in her exhibition “Ocean Floors: Works by Celeste Roberge” at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum at Flagler College in St. Augustine. Roberge went on to fabricate the seaweed boats in different metals, playing with variations on their shape.

The boats were nice, but she wasn’t done yet.

Roberge turned next to using different types of seaweed for cyanotypes, a photographic process that dates back to the mid-1800s. She had come across cyanotypes made by Anna Atkins, a 19th century British scientist, who published Photographs of British Algae between 1843 and 1854. Atkins made her prints on paper that had been sensitized with iron salts. This resulted in the seaweed specimens appearing as bluish-white silhouettes against an intense blue background.

To create contemporary cyanotypes, Roberge consulted Erika Greenberg-Schneider, a French-trained master printmaker who runs the Atelier Bleu Acier studio in Tampa, Florida. In turn, Greenberg-Schneider, who teaches graphic design and printmaking at the University of South Florida, recruited a couple of her students to help produce the pieces.

The end result was an extraordinary series of prints showing diverse examples of seaweed. In one, the weed resembles netting, in another, a brain scan. Writing about them for the exhibition “Celeste Roberge: Cyanotypes” at the University of South Florida at St. Petersburg in February 2014, art writer Jessica Skwire Routhier noted how the prints can seem “mesmerizingly pictorial,” evoking “forests, gardens, or even the elaborate illustrations and decorative motifs of the 19th century Aesthetic movement.”

Roberge has been a fall-through-spring resident of Gainesville, Florida, for the past 20 years, teaching in the University of Florida’s School of Art and Art History. She plans to retire in 2015 and already has started the move back to Maine, gradually shipping the contents of her Florida studio to her home in South Portland. She moved there 10 years ago from her hometown, Biddeford, into a small house with a large barn that is the perfect size for a studio plus storage space.

The many objects currently stored in the barn include two sinks given to her by the Kohler Company after a three-month residency last year in an arts/industry program that is run by the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. The highly competitive program (around 400 applications for 16 slots) offers artists the opportunity to create artworks using industrial materials and equipment.

Roberge tests how well her steel sculpture Body Sea holds sand at Fortunes Rocks Beach in Biddeford. Photo courtesy of Celeste Roberge

Roberge tests how well her steel sculpture Body Sea holds sand at Fortunes Rocks Beach in Biddeford. Photo courtesy of Celeste Roberge

Roberge worked in the foundry, where she cast iron and did some enameling, working with the seaweed boat shape. The work at Kohler was physically “extremely difficult”—everything, she noted, “is heavy”—but she was happy to have the equipment and expertise at hand.

The home in South Portland offers a retrospective of Roberge’s work. Walking around the grounds one encounters Daphne, a black steel and copper sculpture that evokes the wind-blown trees on the North Sea shore of Scotland, where Roberge stayed in the early 1980s. Elsewhere, Forward Bending Cairn is a steel armature representing a seated figure with bent torso and arms stretched out as if in mid-exercise.

This latter piece is part of Roberge’s acclaimed “cairn” series, each of which features a welded steel grid figure or shape usually filled with diverse materials: rocks, oyster or mussel shells, or sand. These pieces are permanently sited at the Portland Museum of Art; the Runnymede Sculpture Farm in Woodside, California; and the Nevada Museum of Art. One of them, Northern Archives, Rising Cairn, graces the cover of Edgar Allen Beem’s ground-breaking book Maine Art Now (1990).

Cairn, which is in the collection of Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor and is based on ancient stone markers found in Europe, was made using welded and galvanized steel and huge granite rocks. Photo courtesy of Celeste Roberge

Cairn, which is in the collection of Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor and is based on ancient stone markers found in Europe, was made using welded and galvanized steel and huge granite rocks. Photo courtesy of Celeste Roberge

Roberge is essentially a conceptual artist, but one whose work doesn’t require you to know the backstory in order to appreciate it. Yes, it is fine to learn that the cairn pieces are based on ancient stone markers found in Europe. In the end, though, this knowledge is peripheral to the awe one feels before her rock-filled giants.

Likewise, understanding the context of the seaweed pieces is fun, but without it, these curious vessels that would sink if set upon the sea remain graceful, poetic, and appealing. Some of them resemble slippers or pea pods—others might be models for the ferry across the mythical River Styx.

This is not to say that Roberge’s work doesn’t sometimes enter the more rarefied air of conceptual with a capital C. Yet even when she sets miniature chairs atop narrow stratified columns or arranges gilded cast-iron pots and pans on the floor, the spirited sensibility, and sometimes humor, of this brilliant and inventive artist remains evident.

Roberge said she wants to seduce the viewer. She described seeing a visitor to Rockland’s Farnsworth Art Museum doing a double-take after touching her Granite Sofa installed in the front foyer and discovering it was made of stone, not fabric. Roberge encouraged the woman to sit on the sculpture.

Her Chaise Gabion, in the collection of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, is also meant to draw the passerby to sit and lounge. The artist calls the chaise longue, whose polished steel framework is filled with 17 75-pound bags of Mexican beach pebbles, “sculptural furniture.”

Whatever she is working on, Roberge finds that the process is all-encompassing. “You become completely absorbed in the thing that’s around you and you forget about everything else,” she explained. It isn’t meditation, it is materialist: focusing on the object and the form that it takes.

Roberge is always thinking about new ideas. She has considered cutting holes in the two Kohler sinks. “What I think they’re going to evoke is looking up into outer space,” she said cryptically. She also wants to do more variations on the seaweed boats and maybe even make a kelp chair.

And Roberge is helping to spread the word about the wonders of seaweed. She and Muhlin co-taught a seaweed cyanotype workshop at the first Maine Seaweed Festival, which took place on the grounds of Southern Maine Community College in South Portland this past August. “The whole festival was all about seaweed,” Roberge reported, adding, “Great fun.”

Carl Little’s most recent book is William Irvine: A Painter’s Journey (Marshall Wilkes).

To see more of Celeste Roberge’s work, visit www.celesteroberge.com.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.