Stellar Art

Stell Shevis approaches her second century with élan

By Carl Little

Shelves in the hallway leading into the central work space of Stell’s Camden studio are filled with containers of powdered glass, called “frits,” which she inherited from Pauly D’Orlando (1915-1978), her best friend in art school and a master enamelist.

Shelves in the hallway leading into the central work space of Stell’s Camden studio are filled with containers of powdered glass, called “frits,” which she inherited from Pauly D’Orlando (1915-1978), her best friend in art school and a master enamelist.

By Carl Little | Photographs by Alison Langley Stell Shevis’s folding business card is handmade, naturally—everything she does has a creative side. Inside it is a primer on enameling, the glass-on-metal medium that has been the focus of her work for 30-plus years. She is an authority on this colorful compound, contributing articles on technique to magazines and attending the Enamelist Society’s biennial conference (next year it will be held at Montserrat College in Beverly, Massachusetts—she can’t wait to take some workshops). She may be 99, but Stell continues to look for new experiences and creative outlets. Stell and her late husband, William Shevis, known as Shevis, were among the mainstays of the postwar Maine art scene, helping to start a number of important institutions, including the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, then in Liberty, now in Deer Isle, and Maine Coast Artists in Rockport (now the Center for Maine Contemporary Art). For the 73 years they were married, they created a wide range of artworks that found collectors across the northeast. Stell knows where everything is in

her studio, from the spoons, dental

picks, and tiny sifters used in enameling

to recycled pieces of aluminum that she

has been experimenting with as a

foundation for enamel pieces.

Stell was born Mildred Estelle Beehner in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1915. The family moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, shortly after her birth. Her father was a metalsmith and later opened an auto business. He loved to fish and would take the family to Maine’s Sebago Lake in the summer. Her mother, Stell recounted, “never worked outside the home, but she certainly worked hard inside.”

Stell was drawn to art at an early age. In addition to drawing and painting paper dolls, she molded mud pies, which she would sprinkle with glass that she had crushed between rocks—a foreshadowing of her later passion for enamel.

Stell knows where everything is in

her studio, from the spoons, dental

picks, and tiny sifters used in enameling

to recycled pieces of aluminum that she

has been experimenting with as a

foundation for enamel pieces.

Stell was born Mildred Estelle Beehner in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1915. The family moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, shortly after her birth. Her father was a metalsmith and later opened an auto business. He loved to fish and would take the family to Maine’s Sebago Lake in the summer. Her mother, Stell recounted, “never worked outside the home, but she certainly worked hard inside.”

Stell was drawn to art at an early age. In addition to drawing and painting paper dolls, she molded mud pies, which she would sprinkle with glass that she had crushed between rocks—a foreshadowing of her later passion for enamel. Connections, 9" x 12",

features small enameled pieces on

an old computer motherboard.

At the Massachusetts College of Art, Stell studied drawing, painting, and sculpture, the latter with Cyrus Dallin, the creator of a number of Boston landmarks, including the Paul Revere equestrian statue in the North End. Her coursework included traditional liberal arts—English, psychology, and the like—but one thing she didn’t learn was how to sell her art. She remembers hauling a portfolio of her drawings into Boston office buildings where she was politely rejected (she wore a hat and gloves in order to look older than her 20 years).

Among her college classmates was an outspoken émigré from Scotland named William Shevis. The pair met in 1933 in their first year; they married in 1938. After spending time in the greater New York City area, the couple moved to Maine in 1945, inspired to try their luck in the Pine Tree State by reading Louise Dickinson Rich’s We Took to the Woods and Maurice Kains’s Five Acres and Independence.

They found a house on 12 acres in Belmont in Waldo County where they set up a barn studio for silkscreening and block-printing cards, calendars and prints, which they sold in New York City and elsewhere. Their four children attended a nearby one-room schoolhouse. The family borrowed books from the State Library’s bookmobile, which came down their road once a month.

Connections, 9" x 12",

features small enameled pieces on

an old computer motherboard.

At the Massachusetts College of Art, Stell studied drawing, painting, and sculpture, the latter with Cyrus Dallin, the creator of a number of Boston landmarks, including the Paul Revere equestrian statue in the North End. Her coursework included traditional liberal arts—English, psychology, and the like—but one thing she didn’t learn was how to sell her art. She remembers hauling a portfolio of her drawings into Boston office buildings where she was politely rejected (she wore a hat and gloves in order to look older than her 20 years).

Among her college classmates was an outspoken émigré from Scotland named William Shevis. The pair met in 1933 in their first year; they married in 1938. After spending time in the greater New York City area, the couple moved to Maine in 1945, inspired to try their luck in the Pine Tree State by reading Louise Dickinson Rich’s We Took to the Woods and Maurice Kains’s Five Acres and Independence.

They found a house on 12 acres in Belmont in Waldo County where they set up a barn studio for silkscreening and block-printing cards, calendars and prints, which they sold in New York City and elsewhere. Their four children attended a nearby one-room schoolhouse. The family borrowed books from the State Library’s bookmobile, which came down their road once a month. The finely done enamel-on-copper piece

Butterfly Treasure Box,

7" x 2" deep, shows why Stell has

become a respected authority on

enamel work.

The two artists became known as Stell and Shevis, teaming up to produce the graphic work, serigraphs, printed scarves, greeting cards, and other items that provided them with a living. They lived close to the land, growing vegetables and raising pigs, goats, and chickens, the latter purchased from Sears Roebuck. They also continuously made art. Stell recalls her children saying, “Why doesn’t Daddy go out and work like other men—he’s always here!”

Over the years Stell and Shevis became a part of a lively art community. Many of the state’s most notable artists were among their friends: ceramists Dennis and Ruth Vibert; writer Lew Dietz and his wife, painter Denny Winters; printmakers Francis Hamabe and Carroll Thayer Berry; and painter William Kienbusch. The pair’s artwork was featured on the cover of the first issue of Down East magazine and on many covers thereafter; and their prints were circulated far and wide through Vincent Hartgen’s traveling exhibitions out of the University of Maine. Stell illustrated Dietz’s Andre, a children’s story about the famous seal in Rockport Harbor.

In addition to being involved with the founding of Haystack (where they both taught) and Maine Coast Artists, they helped found the Maine Art Gallery and Maine Coast Craftsmen in Wiscasset, spurred on by artist Mildred Burrage.

The finely done enamel-on-copper piece

Butterfly Treasure Box,

7" x 2" deep, shows why Stell has

become a respected authority on

enamel work.

The two artists became known as Stell and Shevis, teaming up to produce the graphic work, serigraphs, printed scarves, greeting cards, and other items that provided them with a living. They lived close to the land, growing vegetables and raising pigs, goats, and chickens, the latter purchased from Sears Roebuck. They also continuously made art. Stell recalls her children saying, “Why doesn’t Daddy go out and work like other men—he’s always here!”

Over the years Stell and Shevis became a part of a lively art community. Many of the state’s most notable artists were among their friends: ceramists Dennis and Ruth Vibert; writer Lew Dietz and his wife, painter Denny Winters; printmakers Francis Hamabe and Carroll Thayer Berry; and painter William Kienbusch. The pair’s artwork was featured on the cover of the first issue of Down East magazine and on many covers thereafter; and their prints were circulated far and wide through Vincent Hartgen’s traveling exhibitions out of the University of Maine. Stell illustrated Dietz’s Andre, a children’s story about the famous seal in Rockport Harbor.

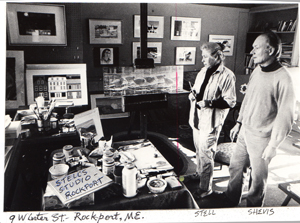

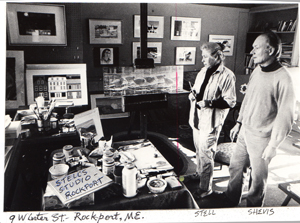

In addition to being involved with the founding of Haystack (where they both taught) and Maine Coast Artists, they helped found the Maine Art Gallery and Maine Coast Craftsmen in Wiscasset, spurred on by artist Mildred Burrage. Stell and Shevis, shown here in their studio in

Rockport, made iconic prints, which they sold

as works on paper and even on fabric. Active

Democrats, they made special chickadee scarves

for their friend Jane Muskie to give away during

her husband Edmund’s vice-presidential

campaign in 1968.

For many winters starting in the early 1950s, the family drove to Mexico. “Shevis really felt the cold,” Stell recalls. “He used to have chilblains.” They could spend six months in Mexico for what it cost them to heat the house in Maine.

In 1964, the Belmont house burned down and the family lost just about everything, including most of their artwork. They moved to Camden, purchased a former inn on Route 1 and established a small shop and gallery for the sale of their art. They turned to limited-edition silkscreen prints, having lost their wooden presses in the fire.

Stell also took up clay. She later painted several hundred watercolor portraits of friends, some of which were shown a few years ago at the Garage Gallery in Rockland. “We never made much money,” she likes to say, “but we lived rich.”

The couple eventually sold their house, which is now the Blackberry Inn, and lived in Rockport for several years before designing and building a home and studio on a lot next door to the inn, where Stell lives and works today. Shevis died in 2010 at age 96. His studio remains as it was, with drawers filled with his marvelous silkscreen prints of downeast scenes and copies of his limited-edition books, including the two-part memoir Stumbling into Maine and Staying (2000), a candid and often humorous account of life in the “hardscrabble backcountry.”

Stell has remained busy.

Stell and Shevis, shown here in their studio in

Rockport, made iconic prints, which they sold

as works on paper and even on fabric. Active

Democrats, they made special chickadee scarves

for their friend Jane Muskie to give away during

her husband Edmund’s vice-presidential

campaign in 1968.

For many winters starting in the early 1950s, the family drove to Mexico. “Shevis really felt the cold,” Stell recalls. “He used to have chilblains.” They could spend six months in Mexico for what it cost them to heat the house in Maine.

In 1964, the Belmont house burned down and the family lost just about everything, including most of their artwork. They moved to Camden, purchased a former inn on Route 1 and established a small shop and gallery for the sale of their art. They turned to limited-edition silkscreen prints, having lost their wooden presses in the fire.

Stell also took up clay. She later painted several hundred watercolor portraits of friends, some of which were shown a few years ago at the Garage Gallery in Rockland. “We never made much money,” she likes to say, “but we lived rich.”

The couple eventually sold their house, which is now the Blackberry Inn, and lived in Rockport for several years before designing and building a home and studio on a lot next door to the inn, where Stell lives and works today. Shevis died in 2010 at age 96. His studio remains as it was, with drawers filled with his marvelous silkscreen prints of downeast scenes and copies of his limited-edition books, including the two-part memoir Stumbling into Maine and Staying (2000), a candid and often humorous account of life in the “hardscrabble backcountry.”

Stell has remained busy. Stell Shevis uses dentistry tools for

some of the precision work she

does in enameling.

“There is always something new to learn,” she said, showing examples of her enamel work. She uses the material to make pins and pendants, brooches, wall works, even magnets. She can use the medium like watercolor, add silver and gold inlays, or apply wire to produce cloisonné. Sometimes she works with stencils; she also works in sgraffito, a technique in which one scratches in the design.

Acrylic paintings and enamel objects hang on the walls in every room in the house. One piece incorporates a motherboard from a computer (Stell is currently on her fourth PC); others feature figures, flowers, sailboats, and stars. In a garage-turned-gallery space, she shows larger pieces, including several enamel works based on dreams and nightmares.

Stell tires of being identified by her age; she “eats right,” doesn’t drive, takes care of herself—and makes art. And then there is her writing project. She is taking a memoir-writing class with the local senior college. Her assorted journals cover just about every surface in her living room.

The more Stell writes, the more she remembers. “I see everything in Technicolor,” she said. She hopes to preserve what has been a remarkable life, for her children and their families, including a passel of grand, great-grand, and great-great-grandchildren, photos of whom cover the refrigerator. Hers is a special story, an adventure in art that continues unabated.

Two poems by Carl Little appear in the 25th anniversary issue of The Café Review. He lives on Mount Desert Island.

Stell Shevis uses dentistry tools for

some of the precision work she

does in enameling.

“There is always something new to learn,” she said, showing examples of her enamel work. She uses the material to make pins and pendants, brooches, wall works, even magnets. She can use the medium like watercolor, add silver and gold inlays, or apply wire to produce cloisonné. Sometimes she works with stencils; she also works in sgraffito, a technique in which one scratches in the design.

Acrylic paintings and enamel objects hang on the walls in every room in the house. One piece incorporates a motherboard from a computer (Stell is currently on her fourth PC); others feature figures, flowers, sailboats, and stars. In a garage-turned-gallery space, she shows larger pieces, including several enamel works based on dreams and nightmares.

Stell tires of being identified by her age; she “eats right,” doesn’t drive, takes care of herself—and makes art. And then there is her writing project. She is taking a memoir-writing class with the local senior college. Her assorted journals cover just about every surface in her living room.

The more Stell writes, the more she remembers. “I see everything in Technicolor,” she said. She hopes to preserve what has been a remarkable life, for her children and their families, including a passel of grand, great-grand, and great-great-grandchildren, photos of whom cover the refrigerator. Hers is a special story, an adventure in art that continues unabated.

Two poems by Carl Little appear in the 25th anniversary issue of The Café Review. He lives on Mount Desert Island.

Shelves in the hallway leading into the central work space of Stell’s Camden studio are filled with containers of powdered glass, called “frits,” which she inherited from Pauly D’Orlando (1915-1978), her best friend in art school and a master enamelist.

Shelves in the hallway leading into the central work space of Stell’s Camden studio are filled with containers of powdered glass, called “frits,” which she inherited from Pauly D’Orlando (1915-1978), her best friend in art school and a master enamelist.By Carl Little | Photographs by Alison Langley Stell Shevis’s folding business card is handmade, naturally—everything she does has a creative side. Inside it is a primer on enameling, the glass-on-metal medium that has been the focus of her work for 30-plus years. She is an authority on this colorful compound, contributing articles on technique to magazines and attending the Enamelist Society’s biennial conference (next year it will be held at Montserrat College in Beverly, Massachusetts—she can’t wait to take some workshops). She may be 99, but Stell continues to look for new experiences and creative outlets. Stell and her late husband, William Shevis, known as Shevis, were among the mainstays of the postwar Maine art scene, helping to start a number of important institutions, including the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, then in Liberty, now in Deer Isle, and Maine Coast Artists in Rockport (now the Center for Maine Contemporary Art). For the 73 years they were married, they created a wide range of artworks that found collectors across the northeast.

Stell knows where everything is in

her studio, from the spoons, dental

picks, and tiny sifters used in enameling

to recycled pieces of aluminum that she

has been experimenting with as a

foundation for enamel pieces.

Stell knows where everything is in

her studio, from the spoons, dental

picks, and tiny sifters used in enameling

to recycled pieces of aluminum that she

has been experimenting with as a

foundation for enamel pieces. Connections, 9" x 12",

features small enameled pieces on

an old computer motherboard.

Connections, 9" x 12",

features small enameled pieces on

an old computer motherboard. The finely done enamel-on-copper piece

Butterfly Treasure Box,

7" x 2" deep, shows why Stell has

become a respected authority on

enamel work.

The finely done enamel-on-copper piece

Butterfly Treasure Box,

7" x 2" deep, shows why Stell has

become a respected authority on

enamel work. Stell and Shevis, shown here in their studio in

Rockport, made iconic prints, which they sold

as works on paper and even on fabric. Active

Democrats, they made special chickadee scarves

for their friend Jane Muskie to give away during

her husband Edmund’s vice-presidential

campaign in 1968.

Stell and Shevis, shown here in their studio in

Rockport, made iconic prints, which they sold

as works on paper and even on fabric. Active

Democrats, they made special chickadee scarves

for their friend Jane Muskie to give away during

her husband Edmund’s vice-presidential

campaign in 1968. Stell Shevis uses dentistry tools for

some of the precision work she

does in enameling.

Stell Shevis uses dentistry tools for

some of the precision work she

does in enameling.Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.