Back When Fat Was Fabulous

In the days of sail, grease was good

Images courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum, National Fishermen Collection

Mealtime on the Gloucester, Mass., fishing schooner Gertrude Thebaud in 1932, would have included plenty of grease to keep up the crew’s energy levels.

Mealtime on the Gloucester, Mass., fishing schooner Gertrude Thebaud in 1932, would have included plenty of grease to keep up the crew’s energy levels.

Good old greasy fat just doesn’t get much respect any more. We used to talk about Fat City, or a well-oiled machine, or a fat wallet, all good things. A digital world doesn’t need oil to keep it running smoothly, and we prize lean and clean in our food, although a well-marbled steak still does not go amiss, and pork belly is apparently well-received in trendy restaurants.

Sure, fat can be too much of a good thing. But for much of mankind’s history, fat signaled celebration. Look at Hanukkah: the oil for the temple lights lasted longer than expected and the yearly observance features potato latkes fried in lots of oil. On the other hand, Mardi Gras, Fat Tuesday, a day to eat fat, signals the start of Lent, a period of animal-fat-less penance.

This photo was taken on a fishing boat in 1987. Note the large crock of butter. Image courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum, National Fishermen Collection

This photo was taken on a fishing boat in 1987. Note the large crock of butter. Image courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum, National Fishermen Collection

Aboard 19th-century American sailing ships, the steward who served the first officer’s cabin picked over salt meat, beef, or pork, to select the pieces with the most fat on them to take aft for the captain and mates to enjoy. Richard Henry Dana, author of the classic Two Years Before the Mast, wrote that the best pieces of meat were “any with fat in them.” The leanest pieces went to the crew, which was no favor. Grease was pure ready-to-burn energy, much-needed by men laboring hard, and doubly important in cold weather when simply digesting it warmed their bodies.

For every thousandth oil barrel filled, Whalers were treated to a batch of doughnuts fried in whale oil-filled try pots. They no doubt relished the flour and sugar, but not as much as the lovely fat in which the doughnuts were cooked.

Always-hungry sailors, who usually were men in their late teens and twenties with prodigious appetites, made dandyfunk, a treat most closely resembling a cookie bar for themselves with pounded hardtack and molasses that they saved from their rations. To make it they had to cadge fat from the cook, and stay on his good side to get oven space to bake it in. In exchange, the crew might offer to wash pots or split wood for the cook, certainly a benefit from the cook’s point of view. The cook also benefitted from saving fat, usually termed “slush,” which he skimmed off after boiling meat. The slush was set aside to be sold ashore for soap making, and the cook was entitled to a percentage of the proceeds. This is the origin of the term “slush fund.”

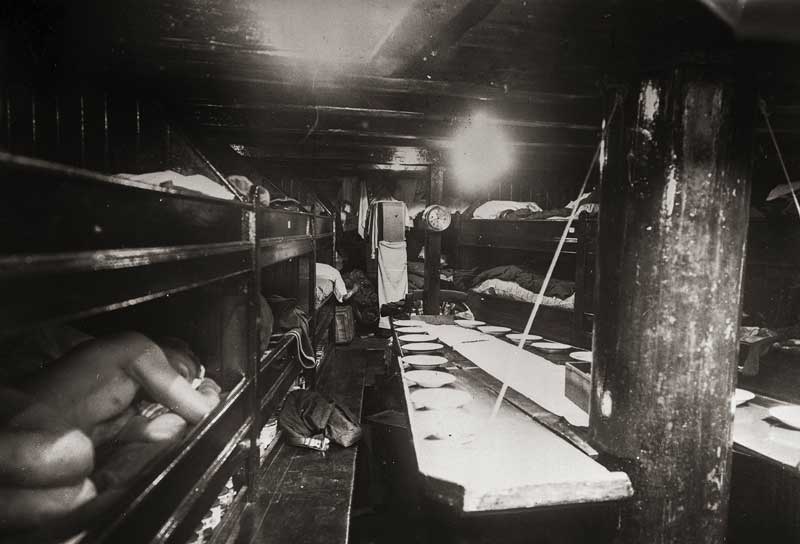

Above and below: These two images, taken in 1937, show the galley and sleeping quarters aboard the Arctic exploration schooner Bowdoin. Fatty foods were especially important for cold-weather sailing. Images courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum, National Fishermen Collection

Above and below: These two images, taken in 1937, show the galley and sleeping quarters aboard the Arctic exploration schooner Bowdoin. Fatty foods were especially important for cold-weather sailing. Images courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum, National Fishermen Collection

The ship’s crew competed among themselves for slush, as well as with the ship itself, which needed grease mixed with tar for waterproofing and lubricating running rigging.

Fishing vessels sailing on the Grand Banks and George’s Banks in the 1800s and early 1900s were always well-provisioned. Besides providing plenty of well-cooked food for the fishermen, the cook might make molasses cookies using drippings. This was partly a matter of economy in using up every morsel of pot-skimmings on board, but it also was to provide an extra boost of energy. Some cooks made doughnuts, too, and pies with lard-based pastry.

Fishermen were not the only ones who ate grease in their cookies. Lumberjacks, who also labored in the cold, were routinely fed wonderfully fatty food, and treated to cookies made with lard. Nowadays, modern Maine guides who take clients on winter camping trips produce rich-in-fat cookies to keep diners warm in the cold and to replace the energy clients burn while snowshoeing up and down hills.

A friend who taught with the Grenfell Mission on the Labrador Coast in the 1960s recounted how she’d come home from school in the cold and dark of winter, open a can of baked beans for her supper, and fish out the little piece of pork to eat right away while the beans were heating on the stove. She recalled how utterly delicious it was then, and how astounded she was later that she ever did such a thing. That pork met her need for fatty energy and warmth.

Which brings us to landsmen who prized fat, like the pemmican-eating First Nations, fur traders, and explorers. Pemmican is essentially dried powdered meat and fruit held together by melted fat, cooled to make a solid block of long-lasting food—an early energy bar, if you will.

Inhabitants of houses with no central heating, from the earliest settlement in Maine to the early 20th century, prized fat for energy and warmth. Pork lard and beef suet appear consistently in early recipes. Housewives used pork fat in generous proportions for sausage making. They would cook the sausage, place it in crocks and cover it with melted fat to seal out the air. They used lard for pie crusts, to fry doughnuts, and in other baking recipes like cookies and cakes. Pork apple pie made with apples and a layer of finely cubed fat salt pork upped the old fat ante quite a bit. Suet chopped up was added to mincemeat, and also to steamed puddings. And don’t forget how much butter was used in early baking.

Once vegetable oil came on the market, we see oil-based cake and muffin recipes in cookbooks like the Maine Rebekahs Cookbook and others across the country. Hydrogenated vegetable oil in the form of Crisco or Spry, diminished the use of lard and butter in some recipes but didn’t reduce the fat content.

Almost no one makes salt pork gravy anymore. Fry out some chopped salt pork. Remove the crunchy bits, and set them aside. Sprinkle on flour enough to thicken the fat in the pan, cook it a few moments, then add enough milk to turn it into a thick sauce. Put the salt pork bits back in and pour over toast or boiled potatoes. “A good supper,” an old-timer told me once, “to plow roads on.” Snowplowing decades ago in the dead of winter in unheated truck cabs meant the driver needed internal heating capacity. And don’t forget that Maine specialty, fat from fried pork or bacon dribbled on simmered slack-salted hake and sprinkled with the crisp bits.

The takeaway? Turn down the thermostat, chop wood, build a stone wall, and eat your bacon with impunity.

Sandy Oliver is a freelance food writer and food historian living on Islesboro.

Corned Hake with Salt Pork Fat and Scrunchions*

If you can’t find corned or slack-salted hake, make your own by acquiring a filet of hake, laying it in a glass or stainless steel pan, and sprinkling it fairly generously with kosher salt. Use more than you would to season the fish for eating it, and aim for a visible but not thick layer on top. Cover with a dishtowel and put in the refrigerator for a couple of days. Remove it, drain off the accumulated liquid and rinse the fish. Proceed with the recipe below.

You can also use salted cod. Soak that for several hours before cooking.

Serve the fish and salt pork with boiled potatoes.

*Scrunchions is an old term for crisp, fried-out bits of salt pork.

Ingredients

About a quarter of a pound of salt pork, chilled until firm

A filet of corned hake, about a pound

Pepper to taste

- Cut the salt pork into very small cubes and cook them in a frying pan over a medium heat. Do not allow to scorch. Drain them, set aside, and reserve the fat, kept warm.

- Put the salt fish in fresh water to simmer gently over a medium heat until it flakes apart. Drain and put on a warm plate to serve.

- Dribble the rendered fat over the fish, sprinkle on the fried pork bits, and serve very warm.

- Add freshly ground pepper to taste.

Serves three to four.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.