Michael Vermette

A Passion for Plein Air

Michael Vermette, shown here plein air painting on the Allagash, was the inaugural Allagash Wilderness Waterway visiting artist. The residency program was established by Maine’s Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry to mark the 50th anniversary of the creation of the scenic waterway. Photo by Troy Sands

Michael Vermette, shown here plein air painting on the Allagash, was the inaugural Allagash Wilderness Waterway visiting artist. The residency program was established by Maine’s Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry to mark the 50th anniversary of the creation of the scenic waterway. Photo by Troy Sands

Plein air painting has been around for centuries, but it was the French Impressionists who brought it to the fore, taking their easels outdoors to capture the changing light. In the open air, Monet and company embraced the immediacy of the experience and their ability to be true to the color in the landscape.

Painting outdoors, said Michael Vermette, one of Maine’s foremost plein air practitioners, “is the greatest teacher because you are observing ever-changing nature and trying to capture the truth of it.” Plein air painting is about “getting close enough [to nature] that the viewer actually enters into the space of the subject through the painting.”

In pursuing that mission to convey the essence of the natural world, Vermette has become one of the pre-eminent painters of the Maine landscape, be it Baxter State Park, Acadia, or Monhegan Island. Over the years he has been able to immerse himself in these iconic places through artist residencies, spending quality time exploring and painting.

Maine Geological Surveyor Bob Johnston (in the bow) and Allagash Waterway Superintendent Matthew LaRoche maneuver their canoe through the white water. Shooting Chase Rapids, Allagash Wilderness Waterway, 2020, oil on heavy linen, 38 by 48 inches.

Maine Geological Surveyor Bob Johnston (in the bow) and Allagash Waterway Superintendent Matthew LaRoche maneuver their canoe through the white water. Shooting Chase Rapids, Allagash Wilderness Waterway, 2020, oil on heavy linen, 38 by 48 inches.

Vermette’s most recent posting, in 2020, was historic: He was the inaugural Allagash Wilderness Waterway visiting artist. Hosted by Maine’s Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry, which established the residency program to mark the 50th anniversary of the creation of the scenic waterway, he spent two weeks in late July/early August living in Dot Kidney’s “amazing cabin” at Lock Dam on Chamberlain Lake.

Wanting to make the most of his residency, Vermette set out to create 50 small paintings in different locations on the 92-mile-long waterway. His subjects were diverse, from a close-up of water lilies on Chamberlain Lake to panoramas of the waterway painted from atop Allagash Mountain. He worked in oil and watercolor, seeking a kind of oneness with the wilderness environment through his art.

One of the stand-outs from the residency is the dramatic Shooting Chase Rapids, Allagash Wilderness Waterway. To create the canvas, Vermette asked Allagash Waterway Superintendent Matthew LaRoche if he and one of his rangers would paddle the rapids after the flood gates were opened at Churchill Dam. LaRoche agreed and chose Bob Johnston, a 37-year Maine Geological Surveyor and ranger to accompany him.

The image Bear Mountain from Pillsbury Island, Eagle Lake, Allagash, 2020, (oil on birch panel, 8 by 10 inches) is an example of Vermette’s direct approach to paint.

The image Bear Mountain from Pillsbury Island, Eagle Lake, Allagash, 2020, (oil on birch panel, 8 by 10 inches) is an example of Vermette’s direct approach to paint.

Vermette and a friend, professional photographer Troy Sands, set up their cameras and got still and video images as the two men shot the rapids, twice. “The figures in this wild river were my favorite subject—not that much different from the rugged lobstermen, lumberjacks, and sporting camp owners of my own family heritage,” Vermette said.

The idea for the painting came from a James Fitzgerald watercolor Vermette owns of two paddlers shooting the rapids on the Penobscot River in a birch bark canoe. Fitzgerald (1899-1971), who painted on Monhegan and in Baxter State Park, is one of his art heroes.

Another high point of the residency was a canoe trip to Pillsbury Island on Eagle Lake, where Henry David Thoreau camped in 1857 and was inspired to write about the Allagash in his book The Maine Woods. Vermette painted Bear Mountain from Pillsbury Island, Eagle Lake, Allagash in honor of his wife, who is a member of the Bear Clan of the Penobscot Nation.

Vermette’s love for oil paint dates back nearly 50 years. When he was studying at the Portland School of Art in the late 1970s, he used to visit the Westbrook College Museum once a week to view the famous van Gogh painting Irises owned by John Whitney Payson. “I never got over the romance of thick paint,” he noted.

His signature bold impasto paintings are made with palette knives, which produce what he calls “descriptive strokes” of “power, motion, and shape.” Following the formula of the Italian old masters, he adds a black oil wax medium that he makes himself. The medium creates a velvety sheen and enhances the viscosity of the paint, which, he said, has the consistency of peanut butter.

By contrast, Vermette’s watercolors feature thinner layers of paint, but bold colors. He loves the transparent washes that create what he considers “a better glow” than oils. Watercolor also brings out the character of the handmade paper—the classic Whatman is his favorite.

In both mediums, Vermette is always trying to increase the brightness of the paint in order to make it appear “more alive.” Because watercolor dries lighter, he will overstate the colors. Oil stays the same, which is ideal for when he wants the landscape to reflect his view of what is there for color. On location, he noted, nature is “in control,” while in the studio he assembles what he has learned from his surroundings. Both experiences are “incredible” and “necessary.”

As he recounted in an interview with the Natural Resources Council of Maine, the Allagash offered an array of subject matter—and adventure. One morning he woke early to paint a watercolor of the sunrise at nearby Marin Cove on Eagle Lake. When he arrived at the portage, he came face to face with a bull moose and his cow, the former staring at him from across the cove for a good 20 minutes. When Vermette finally stepped forward, the pair bolted into the woods.

As part of his residency, Vermette taught a one-day plein air watercolor workshop at Nugent’s Camps on Chamberlain Lake. He came prepared, from PPE supplies to plein air watercolor kits for the nine students. They started at 8 a.m. and finished at sunset, with demonstrations and group critiques part of the offerings.

In his teaching, Vermette draws on 35 years of sharing his love of making art with students at the Indian Island elementary school. Soon after earning his K-12 art educator certification at the University of Maine in 1986, he landed a position as the first art instructor at the school. He has helped organize the Waponahki Student Art Show at the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor.

Vermette had planned to retire this year to paint full-time, but because of the pandemic he has kept teaching, setting up remotely to teach students using Google classroom and a digital camera to film his demonstrations.

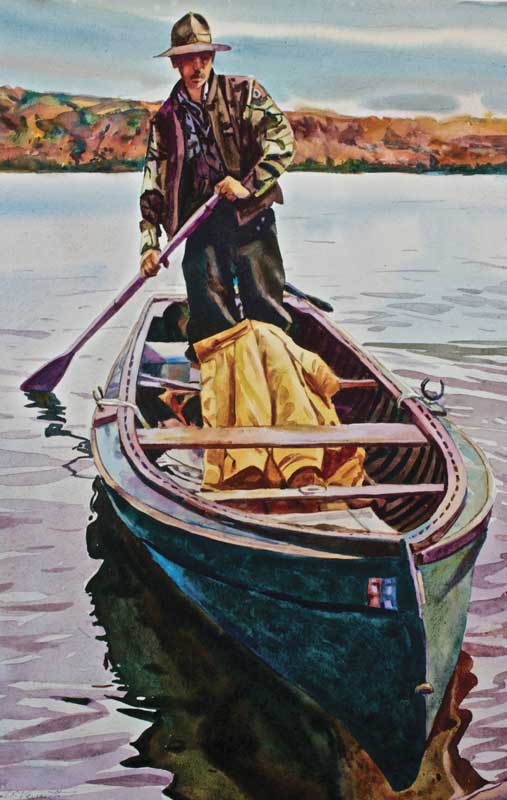

Maine guide Alfred Cooper III lands a canoe on the north end of Katahdin Lake. Maine Guide in a Grand Laker, 2019, watercolor, 24 by 18 inches.

Maine guide Alfred Cooper III lands a canoe on the north end of Katahdin Lake. Maine Guide in a Grand Laker, 2019, watercolor, 24 by 18 inches.

Born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1958, Vermette boasts deep Maine roots. His great-great-grandfather Abel Andrews quarried granite from Rattlesnake Mountain to build the “Stone House” in Stow in the Cold River Valley near the New Hampshire border. His mother was born nearby, at the Brickett Place, which was built around 1830 by Andrews’s brother-in-law John Brickett (it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982).

And then there’s great-grandfather Mark Bradford Crouse, ship carpenter, quarryman, and fisherman/lobsterman out of Cushing who, through his wife Bessie, was related to Christina Olsen of Andrew Wyeth fame. Some of Vermette’s relatives are buried in the graveyard on the Olsen farm.

Vermette came to art early. His family moved to Los Angeles when he was seven; there he was inspired by an uncle, painter Ronald Vermette. He attended the Famous Artists School, an art correspondence school, under his sister Jolene’s name because he was too young. He still has a set of lesson books from the correspondence school.

When the family returned to Maine two years later, they settled in Wiscasset. Vermette’s elementary art teacher, steel sculptor Raymond Shadis, taught him how to draw boats using a figure eight on its side. When he wasn’t teaching, Shadis was a renowned anti-nuclear activist who helped shut down Maine Yankee Nuclear Power Plant. Vermette’s father happened to be a pipefitter in the construction of the nuclear plant. Despite their conflicting views, the two men were good friends.

Maine guide Alfred Cooper III lands a canoe on the north end of Katahdin Lake. Maine Guide in a Grand Laker, 2019, watercolor, 24 by 18 inches.

The family eventually moved to Brunswick. His father worked for Bath Iron Works and his mother joined a travel agency. High school brought new art teachers and early fame: In his freshman year, Vermette won a Halloween window painting contest put on by the local recreation department. His prize: a month’s worth of free art lessons with Polish-born painter Alicia Stonebreaker (1925-1976). Stonebreaker taught him how to paint in watercolor and invited him to join her plein air painting group on outings along the coast. She also encouraged him to visit Monhegan.

When at last he visited that island, the then 17-year-old Vermette experienced a visual encounter on Lighthouse Hill that allowed him, in his words, “to hear from God through nature.” Resolving then and there to be an artist, he enrolled at the Portland School of Art. His mother borrowed $100 from her boss at the travel agency, who was a granddaughter of Governor Percival Baxter—Vermette’s first connection to the park that would become central to his art.

Vermette enjoyed a topnotch lineup of teachers at the school, including Bill Collins (painting), Ed Douglas (painting and drawing), John Lorence (2D design), Joan Uraneck (art history), and Alan Gardiner (watercolor and printmaking). He also remembers English with Franco-American poet Jim Bishop (who had taught Stephen King at UMaine) and Steve Halpert’s literature course. A film connoisseur, Halpert showed foreign films at his art house theater in the Old Port. Vermette remembers watching Bergman and Fellini films.

Since then, Vermette has divided his time between painting and teaching. His art has gained him a dedicated following. He credits his family, teachers, and community for “always making room” for his creativity.

Vermette remains a lover of wild places, returning each year to his favorite locations: Monhegan, Mount Katahdin, Acadia, and now the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. Ready to face the elements, he pursues his plein air passion with a special glint in his eyes and a brush laden with paint.

Carl Little lives and writes on Mount Desert Island. He is a regular contributor to this magazine and to Working Waterfront, Art New England, and Hyperallergic.

Vermette is represented by Yarmouth Frame & Gallery, Lupine Gallery on Monhegan Island, and Gleason Fine Art in Boothbay Harbor where he will have a solo show, “50 PLUS ONE: The First Artist Residency of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway” opening August 6, 2021. View more of his work at michaelevermette.com.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.