Hurricane Island Unveils a New Research Station

Photos by Polly Saltonstall

Hurricane Island’s new field research station is perched on a pier close to the water. Plans for the building include the installation of flowing seawater tanks.

Hurricane Island’s new field research station is perched on a pier close to the water. Plans for the building include the installation of flowing seawater tanks.

Boaters passing by Hurricane Island recently might have noticed a decidedly modern-looking structure perched on one of the island’s old granite piers, just feet from the ocean’s edge. This new state-of-the-art field research station mark’s the island’s new life as a center for cutting-edge scientific research and education in a unique marine environment.

For many years Hurricane Island provided a base for learning life skills in a watery setting as part of the Outward Bound program. More recently, the 125-acre island off Vinalhaven has been home to the nonprofit Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership, which hosts science camps for students and conducts marine research. Current projects include several involving the study of scallops and aquaculture. The island’s location in Penobscot Bay at the confluence of the eastern and western Maine coastal currents and near the discharge of freshwater from the Penobscot River make it an ideal place for research, according to University of Maine marine biologist Bob Steneck.

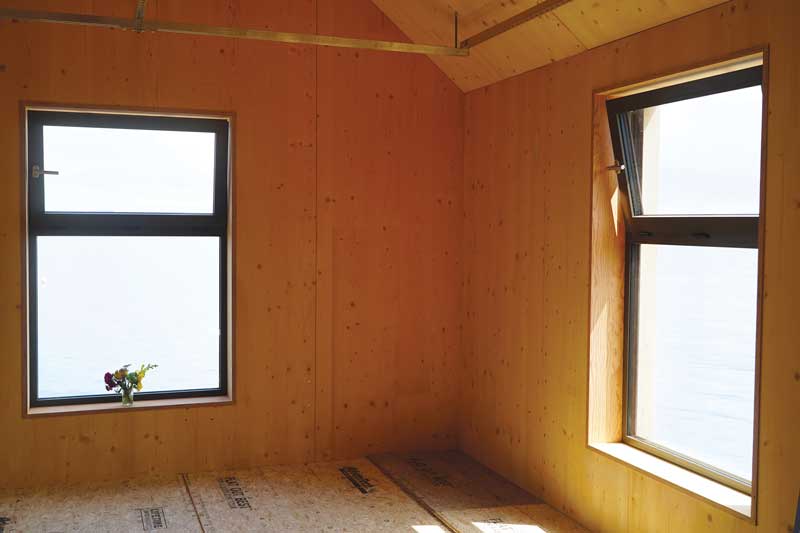

Windows in the second floor lab look out over Hurricane Sound and the waters where students in the lab will conduct research.

Gulf of Maine waters are warming faster than 99 percent of ocean waters worldwide, but there is little data to shed light on the causes and consequences of these changing ocean temperatures, Steneck said. The new research station will serve as a science facility and a hub to connect local students, teachers, scientists, community leaders, and fishermen in shared efforts to better understand the marine environment.

Windows in the second floor lab look out over Hurricane Sound and the waters where students in the lab will conduct research.

Gulf of Maine waters are warming faster than 99 percent of ocean waters worldwide, but there is little data to shed light on the causes and consequences of these changing ocean temperatures, Steneck said. The new research station will serve as a science facility and a hub to connect local students, teachers, scientists, community leaders, and fishermen in shared efforts to better understand the marine environment.

The new building’s construction is as innovative as the research it will enable, according to speakers among the phalanx of politicians, marine biologists, trustees, and supporters, who trekked to the island last summer to celebrate the completion of the new structure. The structure, 1,100 square feet above and 1,100 square feet below, features a passive-house “envelope” that minimizes the building’s power consumption from the solar micro-grid that powers the Hurricane campus, keeping emissions and environmental impact to a minimum.

The new building had not yet been finished last summer as fundraising continued to cover the cost of the $2 million structure. News in late August of a $500,000 THRIVE forgivable loan through the Finance Authority of Maine was a major boost.

The new building had not yet been finished last summer as fundraising continued to cover the cost of the $2 million structure. News in late August of a $500,000 THRIVE forgivable loan through the Finance Authority of Maine was a major boost.

The building was designed and built by Belfast-based OPAL, whose executive partner, Matt O’Malia, was on hand for the August event. OPAL faced major logistical hurdles on the project, including working and delivering material to an unbridged island in harsh side-season conditions. The structure showcases the future role of sustainable Maine forestry products, O’Malia said, explaining that it is carbon-negative because the building materials—cross-laminated timber, glulam beams, and wood-fiber panels—store more carbon than was used to produce them. Sustainable building practices such as these will play a key role in combatting climate change, whose effects will be studied in the lab, O’Malia noted.

“If we can build this on a rocky promontory in Penobscot Bay, we can take this model and replicate it across the country,” he said. “This project proves these buildings are possible.”

The building is insulated with a wood fiber product.

The building is insulated with a wood fiber product.

OPAL’s sister company TimberHP recently began manufacturing insulation in a former paper mill in Madison, using wood-fiber waste from the lumber industry, in a first-of-its kind operation in the United States. The new factory was not yet online when work began on the Hurricane Island structure, which meant its wood insulation had to be imported from Germany, O’Malia explained.

While the structure has been completed, the building still needs to be fully equipped. Plans call for indoor flowing seawater tanks, which will allow scientists and students to interact with species in a controlled environment just a few hundred yards from the island’s experimental aquaculture site where scallops, kelp, mussels, oysters and other specimens can be grown or collected from the wild.

Educational projects on the island include the development of a year-long high school curriculum in partnership with the North Haven Community School of interdisciplinary coastal study known as the Offshore Year, with emphasis on environmental science, civic engagement, and the arts.

Hurricane Island trustees and supporters looked as Maine Gov. Janet Mills cut the ribbon, actually a fishing rope, at last summer’s ceremony for the new field research station.

Hurricane Island trustees and supporters looked as Maine Gov. Janet Mills cut the ribbon, actually a fishing rope, at last summer’s ceremony for the new field research station.

Comparing the vast expenses of research vessels to the cost-effective opportunities of a centrally located and sustainable research station, Steneck said research around aquaculture at facilities such as this one is key.

“What I’m seeing now throughout the state of Maine and the world is the rise of aquaculture, which has all these new questions that arise from it. We’ve got to have the science to know what’s going on and that’s why I’m so passionately in favor of this program,” he said.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Hurricane Island was home to a thriving granite quarrying business, which collapsed suddenly leaving a ghost town on the island. Maine biologist Rick Wahle compared that collapse to changes now affecting Maine’s fishing communities. The lobster fishery, which Wahle called the country’s single most valuable species fishery, faces unprecedented challenges, as a result of ocean warming. Research stations like this one, he said, will be key to finding ways to diversify the fishing portfolio.

Polly Saltonstall is editor of this magazine.

For more information about Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership and the Field Research Station visit hurricaneisland.net.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.