A Stonington Sea Captain’s Legacy

Papers stored for years by descendants of John Sherman Hoyt included a photo of Capt. Scott and Byron Stookey aboard the Stella. Image courtesy Ben Emory.

Papers stored for years by descendants of John Sherman Hoyt included a photo of Capt. Scott and Byron Stookey aboard the Stella. Image courtesy Ben Emory.

Hard by the door to the marine room of the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society is a wall plaque dedicating the space to the late Capt. Walter E. Scott Sr., a founding member of the society. The captain’s interesting maritime life and prolific poetry and prose have faded from memory in recent times, but a file of papers long buried in southern New England and brought to light in 2020 adds to his fascinating story. Frustrating but tantalizing is that even more information about this talented man and his lost writings, including his autobiography, may still exist but have yet to be found.

Nineteenth century Maine families were often large. Few, though, were as enormous as John Scott’s, reported to be the largest clan on Deer Isle, with 21 children, 19 of whom were boys. Seemingly, the mother of all was Fannie Dow Scott, who must have been a remarkably robust woman. Walter, one of the 21, and born on May 9, 1887, spent his earliest years on Pickering Island off Deer Isle’s western shore, where his father was the island’s resident year-round caretaker until 1891. Walter would later write that on July 15 his mother took her infant son home to the island.

Like many Deer Isle seamen, Walter Scott went “yachting.” Histories of the America’s Cup competitions have highlighted how valued crew members from Deer Isle were aboard the large cup defenders of the time. Scott, though, chose a different course and landed a command of a smaller vessel but also one of impeccable pedigree. Beginning at about age 40, he was the professional captain for a decade aboard the 47-foot John Alden-designed schooner the Stella, owned by American industrialist John Sherman Hoyt. The Stella’s home port was in Darien, Connecticut.

Scott’s years as a yacht captain have until now been little reported, even by himself. But recently, papers related to his years as skipper of the Stella were brought to light by Hoyt’s grandson, the late John Hoyt Stookey, a Brooklin, Maine, summer resident, instigator of the “green lobsterboat project” of the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, and my brother-in-law.

Stookey had been given the papers—newspaper clippings, poems and two letters from Scott to Hoyt, all contained in an old manila envelope, by his mother, Hoyt’s daughter. He in turn, had given them to me, and I intend to donate them so they can be added to the historical society’s other material on Scott.

As an aside, John’s younger brother, Byron Stookey, and his wife, Lee, retrieved from other files a photo of Scott aboard the Stella with Byron, then a little boy, seated next to him; Byron is identified on the back by a note in his mother’s handwriting.

Image courtesy Ben Emory

By the time he set foot on the deck of the Stella, Scott already had spent half a lifetime as a mariner. Newspaper and magazine articles in the Stookey files and in the collections of the historical society shed light on his life before the Stella. These articles indicate that at age 13 Scott left his island home to seek opportunities on the Boston waterfront, working on coasting schooners before, at age 15, signing on with a sailing ship and rounding Cape Horn. During this period, he spent seven years sailing the world’s oceans, including voyages to China and Australia. But at the time, steam power was taking over the waves, and, no doubt, being closer to home called.

Image courtesy Ben Emory

By the time he set foot on the deck of the Stella, Scott already had spent half a lifetime as a mariner. Newspaper and magazine articles in the Stookey files and in the collections of the historical society shed light on his life before the Stella. These articles indicate that at age 13 Scott left his island home to seek opportunities on the Boston waterfront, working on coasting schooners before, at age 15, signing on with a sailing ship and rounding Cape Horn. During this period, he spent seven years sailing the world’s oceans, including voyages to China and Australia. But at the time, steam power was taking over the waves, and, no doubt, being closer to home called.

Scott began his career in steam as a deckhand, including working on the sidewheeler Penobscot. According to Penobscot Bay Mount Desert and Eastport Steamboat Album by Allie Ryan, he rose to become the third captain of the City of Bangor, long known as the “Queen” of the steamers, providing passenger and freight service between Bangor and Boston. Administrative roles followed, as the Boston-based marine superintendent of the Eastern Steamship Co. before going to New York to work for other steamship companies and preparing vessels for World War I service.

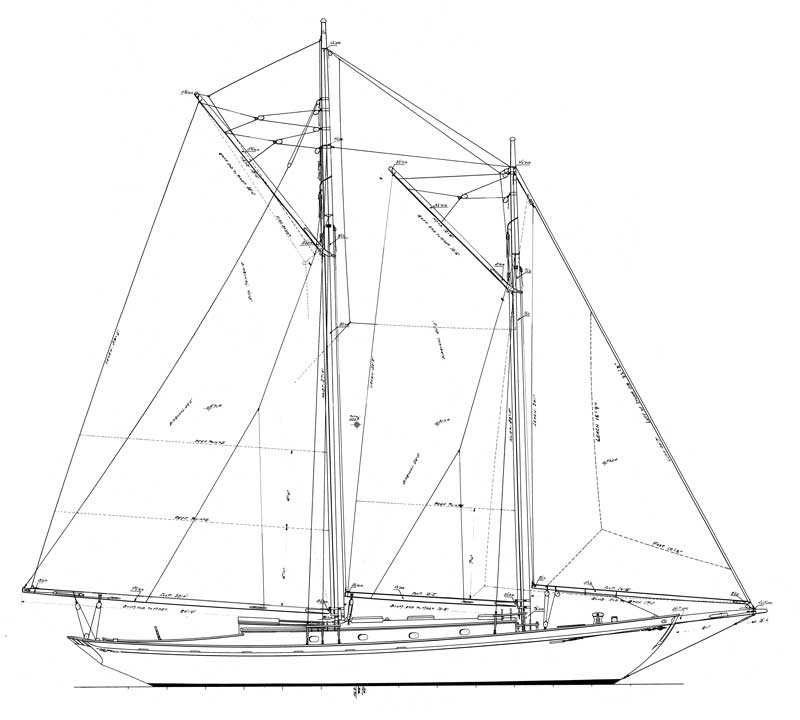

By the mid-1920s Scott became known to New York businessman, investor, and philanthropist John Sherman Hoyt, who was an avid yachtsman and a founder of the Boy Scouts of America and the YMCA. Some years earlier, Hoyt had encountered the future great naval architect John Alden, who during a teenage escapade-type of cruise in an open sailboat, had sought refuge from bad weather at Hoyt’s dock on Long Island Sound. The book John G. Alden and His Yacht Designs, by Robert Carrick and Richard Henderson, recounts that visit, which led years later to Hoyt asking Alden to design him a schooner. Alden did so, and the Franklin G. Post yard of Mystic, Connecticut, built the Stella. No sisterships were built, but she appears to be a slightly larger version of famed design 309, many of which were launched. The Stella’s measurements were 47 feet, 5 inches LOA; 35 feet, 9 inches on the waterline; 12 feet, 9 inches beam; and 4 feet, 6 inches draft. Scott became the professional captain, believed to be the only captain Hoyt ever had aboard the Stella.

Two letters from Scott to his employer and one poem by Scott about his passion for the schooner Stella have surfaced in the Stookey files along with others of the 740 poems he said he wrote, many published in two small volumes entitled Poems of Coastal New England and in Stonington’s Island Ad-vantages newspaper. He also wrote columns on maritime affairs for Rockland’s Courier Gazette and then Island Ad-Vantages.

The depth of Scott’s prose and poetry is extraordinary considering what he considered his weak education. He wrote to Hoyt from Deer Isle on December 2, 1938, “I try to help as much as possible in civic affairs for the betterment of the community and schools that my children shall not be deprived of that which I wanted more than anything else in the world, a good education, being deprived of this.”

Not only was Scott an advocate for good education on Deer Isle, he also was a keen observer of wildlife and a voice for conservation. In the same letter he wrote, “Grouse are quite abundant and now the snow has come they have taken to the birches for their food and as birch buds are plentiful they too can survive a hard winter.” He wrote also about working to get a resident game warden on Deer Isle, hoping to give “him a salary sufficient to enable him to devote his entire time winter and summer in protecting and caring for all species of wildlife on the island.” The game warden was to control what Scott called “the ruthless game killers.”

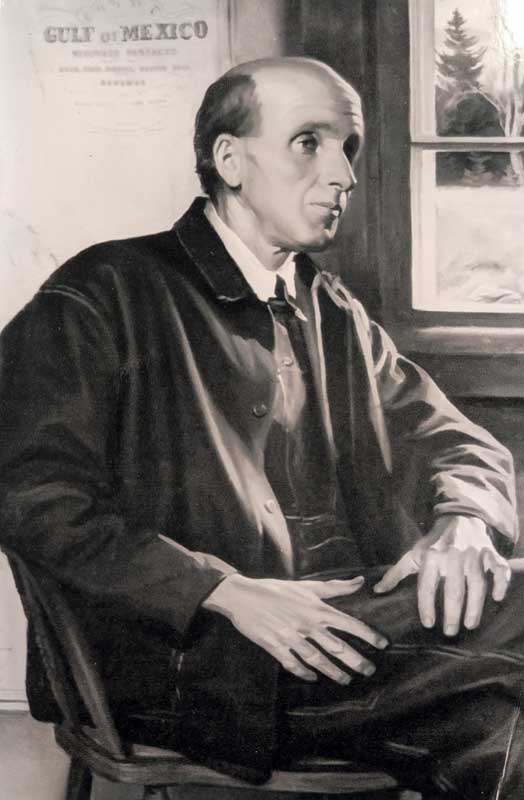

A painting of Scott by Stanislav Rembski (1896-1998) is in the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society’s collections. Image courtesy Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society

A painting of Scott by Stanislav Rembski (1896-1998) is in the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society’s collections. Image courtesy Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society

Probably never published was a typed poem dated December 30, 1936, which Scott included with a letter to Hoyt a week later. He titled it “Shennamere,” the name of Hoyt’s Connecticut estate. The following excerpted stanzas express his love for the schooner he commanded there:

“This dock shelters the dearest of all / That trim little schooner with masts neat and tall / She rests on the water as graceful as a gull / She is a picture of beauty with her black painted hull. Her bright varnished deck houses with bright polished rail / Clean khaki coverings over a neatly furled sail / The two bower anchors securely in place / Leaves memories before me that I cannot erase. That cozy forecastle is the place of my dreams / I am contented and happy in the Stella’s forepeak.”

What good fortune for Hoyt to have a professional captain so devoted to his schooner! It is sad, though, that there are no known photographs of the schooner, not even in Mystic Seaport files or at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which has the John Alden archives; MIT could, however, provide the sail plan, which shows a lovely craft indeed, with sweet lines and impressive rig.

Scott’s December 2, 1938, letter to Hoyt makes clear he planned to be back aboard the Stella the following summer. By then he had been captain of her for a decade, but another season may not have happened. According to Hoyt’s older grandson, John Stookey, Hoyt lost his money in the late 1930s, and the schooner “was perhaps burned but anyway scuttled in the middle of Long Island Sound.” That was truly a tragedy, if true, for the schooner, the family, and perhaps most of all, for the devoted Scott. Whether purposeful destruction really happened is a mystery. The MIT Museum’s website aldendesigns.com lists Caribee as a subsequent name of the Stella, yet research in Lloyd’s Register of American Yachts has not found a schooner under that name.

World War II followed closely after Scott’s years aboard the Stella. During the war, according to an article on Scott by Clayton Gross in the August 19, 1982, Island Ad-Vantages, Scott represented the British War Ministry and in New York City headed a war bond drive. He returned to Deer Isle after the war, to

his home, which he called “Dunroamin Cottage.”

In the company of his wife, Kathryn Mae McVeigh, with whom he had had two children, Walter Jr., and Rosamond Scott Eaton Dow, he devoted his later years to civic affairs, marine research, and writing. A letter in 1956 from Scott to the Maine State Library in Augusta, found online in the library’s special collections along with later letters, refers to his autobiography and says that “its last chapter is not as yet complete.” But in 1962 he wrote to the library, “I have decided that I would use a part of this manuscript in a book that would cover historical facts concerning steamboats and sailing ships of our New England coast.”

The last letter this author has seen from Scott was dated February 7, 1963, also written to the Maine State Library, and he mentions making “notes for the completion of my book.” Do his manuscripts for his autobiography and for his book on steamboats and sailing ships still exist somewhere? If so, where?

The Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society archives include a large ledger-type book of Scott’s filled with a mish-mash of navigation calculations, poems, and at least three pages of hand-written autobiographical information. Notably, many pages were clearly torn from the book. Might they have been the manuscripts for the books referred to in his letters to the Maine State Library?

Captain Walter Scott’s eyesight was failing due to cataracts, and there is no evidence that a book was published. Much like the supposed demise of the schooner Stella, the fate of the manuscripts remains a mystery. What we do know is that Scott died in Prospect on March 13, 1965, at the age of 77. And so, the search for his missing papers continues to intrigue.

✮

Ben Emory splits his time between Salisbury Cove and Brooklin, Maine. He is the author of Sailor for the Wild—On Maine, Conservation and Boats, published by Seapoint Books.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.