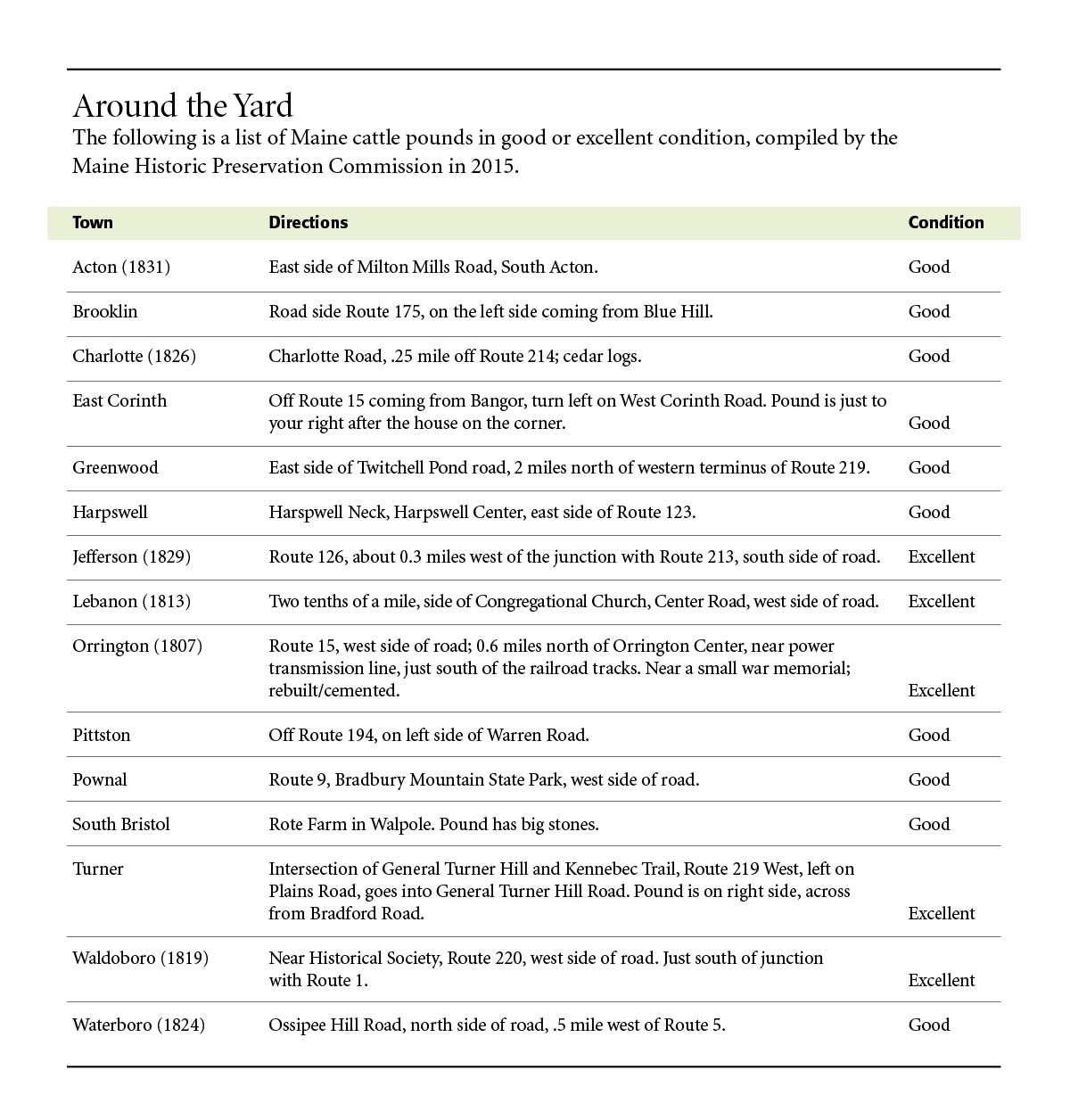

When Cattle Pounds Kept Strays at Bay

The Brooklin cattle pound dates back to 1851 and was restored in 1976. Photo by Jennifer McIntosh

The Brooklin cattle pound dates back to 1851 and was restored in 1976. Photo by Jennifer McIntosh

If you’ve spent any time rummaging around in rural Maine towns, you may have come across an impressive stone structure, 5 to 7 feet tall, that resembles a wall of some sort. Some are circular with a single gate, others square. Some have mortared walls with capstones, obviously built by skilled masons. Others are dilapidated, but with gigantic stones. All are at least 150 years old and a few date back to the 1700s.

They are town pounds, a relic of Maine’s agricultural past, when free-ranging horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs were common—and were also a serious threat to neighbors’ gardens and crops. Such a threat, in fact, that the first time legislators assembled after Maine gained statehood in 1820, they passed laws authorizing every town to build a pound and appoint a pound keeper. One year later, they went further, mandating that every town establish a pound.

The Orrington pound (1807) still has its original iron gate. Sitting close to Route 15, it was damaged in 2022 when a car left the road. It has since been repaired. Photo by Steele Hays

The Orrington pound (1807) still has its original iron gate. Sitting close to Route 15, it was damaged in 2022 when a car left the road. It has since been repaired. Photo by Steele Hays

There are at least 52 town pounds remaining in Maine, according to the Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Many are in poor shape now, but five are rated in excellent condition and seven are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The 1829 cattle pound in Jefferson is one of the finest examples. No roadside sign marks it, only a painted inscription over the stone lintel that still tops the entrance gate: “Built by Silas Noyes in 1829 for 28 dollars.” Its circular walls appear just as upright and intact as when the pound was built. Today only woods surround it, no farms or houses in sight.

Pounds offer us a portal to the past. If you enter through the gate, sit quietly with your back against the cool stones and let your imagination run, you can almost hear the sounds that reverberated within the walls 190 years ago. The metallic clink of a cow bell, the snorting and huffing of horses, the grinding sound of teeth chewing hay or grain. And the human sounds of the pound keeper shouting commands, using his wooden staff to direct another animal through the narrow gate; or the sounds of a farmer leading his stray animals home after grudgingly paying fines and fees to the pound keeper.

One Maine history student who writes the public blog Christina Explores Maine probably expressed the feelings of many Mainers about pounds when she wrote: “I have noticed this thing sitting on the side of the road since I was young… I have never given much thought to it growing up, just thinking it was some weird stone thing that no one really cared about.”

Some people do care about them.

With its high walls and secluded site, the Jefferson pound is one of the most impressive in Maine. It was built in 1829 at a cost of $28.

With its high walls and secluded site, the Jefferson pound is one of the most impressive in Maine. It was built in 1829 at a cost of $28.

“If you are interested in history and what was going on in Maine’s early settlement period, pounds are pretty fascinating,” said Michael Goebel-Bain, National Register & Survey coordinator with the Maine Historic Preservation Commission. “The biggest threat to our remaining pounds is physical decline. They are returning to the wild. Trees are growing up in the center. They’re at risk of disappearing.”

It is hard for us today to appreciate the effect of stray cattle invading a garden or grazing in the wrong pasture. But for families on subsistence farms, the winter’s food supply for both humans and animals was at stake. In addition, in certain seasons male animals on the loose created another problem: it was important for owners to be able to choose which male bred with which female.

We don’t have to rely on our imaginations to travel back in time to when pounds were important hubs of activity. In a few cases, we can read the daily written logs left behind by pound keepers in their official registers. Those men were often colorful characters, tough and self-reliant. When they captured stray animals or when a local farmer brought in someone else’s strays, the pound keeper would write an entry in his log as well as an announcement to be posted in the nearest newspaper or tacked up on the courthouse door.

A farmer could demand payment for damages from an owner’s animal, such as in this entry from the Orrington pound keeper’s log: “To Samuel Pierce pound keeper of Orrington the undersigned Henry French commits to pound a bay-collared stud horse with a white stripe in the forehead four or five years old which he found in his enclosure doing mischief on the 27th day of October and he demands of the owner twelve dollars with all the unpaid fees.” It was dated and signed, October 27, 1846.

You don’t need a time machine to take a trip to the past. Visit a pound. The five pounds considered to be in “excellent” condition are in Orrington, Jefferson, Waldoboro, Turner, and Lebanon.

✮

Steele Hays lives in Blue Hill and is a part-time marketing director and writer.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.